|

|

Post by dodger on Aug 1, 2013 10:28:51 GMT

On Your Marx…Economicsimarxman.wordpress.com/2013/08/01/on-your-marxeconomics/Posted on August 1, 2013 by imarxmanAll commodities get their value from the amount of labour required to produce them. It is human labour that is the source of human wealth. The inherent labour-created value in any commodity is realised when it is exchanged.

So, a commodity requiring 5 hours of labour to produce could be swapped, bartered, for 5 commodities, each the product of 1 hour’s labour time.

This exchange-value is, in modern society, expressed in monetary terms. While in individual cases it may not be precisely represented, across the whole of production and exchange there is a general equivalence.

Many factors affect actual prices at which commodities are exchanged; yet the basic factor remains, the only source of exchange-value is labour. Because this relationship is not immediately apparent it can escape the popular consciousness.

This suits the wealthy because a common appreciation that labour is the source of wealth would pose an obvious contradiction. Why is it those who provide the labour, the workers, are not the richest?

The answer, simply stated, is that the money (wages) paid to a worker does not correspond to the amount of wealth his or her labour creates.

For example, for an eight hour shift a worker receives the monetary equivalent of the value of 4 hours labour. The other 4 hours labour produces value appropriated by the employer. This is called surplus-value.

Despite such obfuscations as references to a middle class, there are in fact only two classes in society, those who are paid wages and those who pay wages. Those who pay wages own the means of production, factories, technology etc., and take the surplus-value.

It does not mean such people are evil as the present economic system can only function in this way. Exploitation of workers is an economic requirement and cannot be moralised away.

Nor can there be any meaningful concept of there being a ‘fair’ profit. Firstly, who is to judge fairness, the worker or the employer? There is only one law in this context; make as much profit as possible.

All the means of production (land, factories, machines, mines etc.) are given the general name of capital. Capital is wealth from which greater wealth can be generated through the employment of labour. Without labour, capital is moribund.

The owners of capital are the gatekeepers of wealth and power because without the means of production workers’ labour power is moribund. Unless, of course, the workers realise their labour is crucial and seize the means of production and use their labour power on their own behalf.

Capitalists, the owners of capital, are dependent for their wealth creation on the labour power of workers. Conversely, workers are not dependent on the capitalists as it is not necessary for them to own capital for wealth to be produced. Capital could be the common wealth of society.

Capitalism can only continue for as long as workers allow it. The working class has, for as long as capitalism has existed, recognised its own crucial economic necessity. It created trade unions through which it could better bargain with capitalists due to its ultimate sanction, strike, the withdrawal of labour crucial to profit making.

The relentless drive for profit leads capitalists to claw back any gains the working class make whenever or however they can. Trade unions remain vital to protect and even enhance the economic position of workers.

Modern capitalist society has become very complex, with finance capital (the controllers of the wealth of the world) having become dominant over manufacturing capital. However, future values (wealth) can only be created through manufacture.

It is often claimed workers have a direct stake in capitalism through their pension funds being invested in capitalist enterprises. However, a pension is the deferred part of a worker’s wage and this is a temporary appropriation of that portion, transferring it back into the hands of finance capitalists to use as they see fit.

Any benefit accruing to the worker is negligible compared to the profits made by capitalists through investing what is not their money. Should that investment go wrong it is the worker who looses out through a reduced or even negated pension.

Much of what is presented in today’s media as economics is mere obfuscation, whether intentional or otherwise. The essentials remain the same now as they were when Karl Marx identified them in the nineteenth century.

Your are either a capitalist, the owner of capital, or a worker, a seller of your labour power. If the latter, you will receive less than the value your labour creates as a wage or salary. The surplus-value will be taken by the capitalist.

The ownership of the means of production (capital) may be somewhat more obscure than in the days of the local mill owner, but that does not change the essential relationship between capital and labour: the former must exploit the latter.

Only when workers realise they could possess both capital and their labour power, with no need of capitalists, will this change.

About these ads

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Aug 1, 2013 14:08:53 GMT

Basic Economics – A Marxist Summary

imarxman.wordpress.com/2013/05/15/basic-economics-a-marxist-summary/

Posted on May 15, 2013 by imarxmanWealth is created through the production and exchange of commodities. A commodity being an object made to satisfy a human need, i.e. it has use-value. All commodities begin as raw materials that in an unused state have no intrinsic value.

Only when materials are extracted and fashioned do they gain value. Through the process of manufacture commodities gain value according to the work (labour power) required for production.

Finished commodities only realise their value when exchanged for commodities of like value. Money, itself a commodity, is the medium by which such transactions take place and respective values are expressed.

Wealth is the sum total of value created in a given context expressed in monetary terms. Wealth becomes capital when invested in further stages of the productive process enabling more value to be created.

The owners of capital invest in the means of production: raw materials, technology, premises etc. However, none of these can create value without the vital ingredient, labour.

Workers, who do not own capital or the means of production, make their living by selling the one element they do possess, labour power. They sell a quantity of labour power, measured in hours, in return for wages.

Wages must, at least, cover the cost of sustaining workers, but not be so high as to consume most or all of the value created during production. So, workers are employed for shifts that are longer than what is required to produce the value of wages.

For example, if a worker must work 4 hours for his labour to cover the cost of his wages, he is then required to work a further 4 hours, the value of which he does not receive.

This latter 4 hours produces surplus value, that is, value beyond what is required to sustain the workers.

Once the value of the subsequent commodities has been realised through exchange (sale) the worker receives his share of that value (4 hours worth) as a monetary sum, leaving the surplus value in the possession of the original capital owners (capitalists).

From this surplus value other costs are met; purchase of materials and technology, rent, transport etc. Whatever then remains, once all expenditure has been covered, is profit.

As technology has advanced, so its cost has increased markedly. To begin a productive enterprise requires large injections of start-up capital, more than is usually available to individuals. This capital has to be borrowed.

Financial institutions developed through the industrial revolution, becoming evermore important as the source of capital. Today, due to the huge amounts of capital they control, such institutions have become primary in Britain.

In simple terms, industry borrows capital from financial institutions, either banks, share floatations or both, which has to be repaid along with a measure of interest on top.

The interest comes from the surplus value created by the productive process once workers’ wages have been covered: it is created by the labour of the workers. Indeed, the initial capital loaned, or invested, is a sum previously produced through the creation of value by labour power.

Workers are paid to sustain them and enable the productive, value creating, processes to continue. Most of their portion of value created is paid as monetary wages. However, some of that value is deferred, to be collected after retirement in the form of pensions.

Capital for pensions may be “stored” in financial institutions that use it for investments. Or, pensions may be paid directly from value created in the present: today’s pensioners being paid through the labour of those presently working.

The whole process of creating value depends on production, the making of commodities for use. It is a social arrangement whereby existing capital (previous labour) is brought together with workers’ labour power to enable productive processes to take place.

Industries are the particular forms through which specific commodities are produced to meet human needs. Technology is developed to make these processes as efficient as possible and it is a function of an industry to make use of such technology to enhance the labour power of its workers.

Debt is intrinsic to capitalism: industrialists borrow capital from finance capitalists, thus placing themselves in debt. Workers also want to buy commodities, but often do not have the income to do so. For large items, house or a car, they also borrow from financial institutions and are then in debt.

Over the last three decades or so, financial institutions have encouraged workers to buy commodities through borrowing, using credit cards. This is effectively spending future wages now and has massively increased personal debt. All debt is really using future value in the present.

Credit (debt) has also been a factor in discouraging workers from fighting for better wages by making lifestyle improvements a personal rather than a collective notion. Personal indebtedness is an influence if strike action is being contemplated due to subsequent income loss adversely affecting debt servicing and credit rating.

Marxism is the systematic analysis of how a given society functions according to its basic economic arrangements. Britain was the first industrial capitalist country, which gave rise to the working class.

Marxism demonstrates how finance capitalism has supplanted manufacturing capitalism in Britain today, even though it only moves value (wealth) around and does not create it.

By coming to understand how capitalism works the working class will be in a position to formulate how it is affected and what needs to be done to make the changes required for it to make best use, on its own behalf, of the value of which it is the only source.About these ads

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Aug 5, 2013 9:02:17 GMT

Horsemeat: A Taste of Capitalism

Posted on February 12, 2013 by imarxmanEverything people need to live – homes, household technology such as washing machines and vacuum cleaners, TVs and smart phones, clothes and the car at the door – are all commodities.

Quite simply, a commodity is anything made for human use. Commodities are produced in order to make profit, and are bought by people wanting to make use of them. This system of production and sale for profit is called capitalism.

Its workings have been graphically illustrated recently by the horsemeat in the beef scandal. A number of products sold through supermarkets have been exposed as containing equine rather than bovine flesh as advertised.

The ConDem coalition has publicly stated its outrage at this cross contamination and made a number of vague statements about this not been allowed to ever happen again. This from a government cutting funding for inspections and vociferous about slashing “red tape”: the argument being producers are overburdened by too much regulation.

Supermarkets have been quick to apportion blame to their suppliers, who seem to be scattered across Europe, making supervision and tracking of foodstuffs difficult. However, this does not exonerate the supermarkets.

While they may have sold horsemeat-tainted products unintentionally, their reckless pursuit of ever increasing profits are the root of the problem. Since 2008, through the worst economic crisis since the 1930s, the big 4 – Tesco, Asda, Sainsbury’s and Morrison’s have made over £26.5 billions profit.

How is this possible when incomes of shoppers have been frozen and in many cases cut? The answer is simple: if people have less money to spend profit margins are maintained by reducing the cost of commodities.

Income and price play crucial roles in determining the supply of commodities. Prices cannot be greater than available incomes can afford, otherwise commodities won’t be sold, so no profits will be made.

If profit is to be maintained without increasing price beyond income levels then cost of production must be reduced. Producers must find ways of cutting their costs otherwise the supermarkets will drop them.

All this at a time when globally meat and grain prices are rising, making beef an expensive ingredient. If suppliers, therefore, can find a cheaper alternative that won’t be detected by the consumer, then production costs can be reduced.

During a recession wage levels are held down as a matter of course, which means costs must be trimmed elsewhere in the production process. Similarly, ground rents are frozen leaving the raw materials as the source of cost savings.

There has been some suggestion that some of the horsemeat has come from slaughtered wild horses or even a surplus created by the recent Romanian law banning use of horses for vehicle propulsion. Animals largely left to fend for themselves or surplus to requirement become cheap raw material.

This is exactly how capitalism works; the one and only purpose for producing anything is profit. It’s what commodities are primarily for, to supply a human need only so a profit can be made.

So, if there is a human need in a time of austerity (poverty caused by recession) for “value foods”, supermarkets will supply them. Consequently, manufacturers of “value foods” look to cut costs to make profits from what they sell to supermarkets.

The next time a politician is waxing lyrical about free markets, this is what is actually meant. “Bonfires of the quangos” is a euphemism for reducing regulation to allow producers to operate unchecked.

Because capitalism is so rapacious as to be devoid of moral standards, the working class has had to press through its collective power for controls. In the early days of capitalism and the Tommy shop, workers’ food was frequently adulterated to lower costs and increase profits.

Capitalism is presently demonstrating that, fundamentally, nothing has changed. Whether it’s best beefsteak or a horsemeat “beef” burger it is a commodity produced for the sole purpose of making a profit. If it takes adulteration to do so, then so be it.

Capitalism requires confidence to survive. The financial crash was caused in large part by institutions losing confidence in international transactions. Similarly, commodity markets need the confidence of the consumers.

So supermarkets and politicians will, for a while, make great play about how they will protect the public good from now on. This is not a concern for public welfare, but fears for profit margins.

However, they cannot change how capitalism operates, even if they wanted to. Of course, they don’t have any interest in changing the nature of capitalism as they are committed to the continuing process of supplying commodities for maximum profit.

As long as capitalism exists so must commodity production: even if stringent laws are enacted the profit motive will win out. Consider the wealth of the world’s illegal drugs cartels.

The concern has to be that next time whatever is the adulterating agent introduced in pursuit of profit; it will be somewhat more harmful. The British may choose not to eat horse, but doing so will do them no actual harm.

Nonetheless, it has demonstrated how easily it was slipped into foods sold in Britain. What if the next source of a cheap alternative turns out to be contaminated with something dangerous? Cars with dodgy brakes can be recalled, but food with dodgy ingredients cannot once consumed.

Shoppers are workers; it’s from their incomes that supermarkets accrue their profits. Workers must exercise their collective power to demand proper regulation and inspection of foods, with strict controls over what is imported. If European Union competition law forbids such constraints then there’s another reason to leave the EU.

imarxman.wordpress.com/2013/02/12/horsemeat-a-taste-of-capitalism/ |

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Aug 5, 2013 14:52:50 GMT

In the days before wireless and television, and there was no money for newspapers, the poor, unsullied by propaganda, except for that of the priests, expressed in their ballads their opinions of the state of the economy and their feelings about their "betters". Here are a few examples.

"The Tories in Dudley have cast in their mites

In order to sup off rich cow-heel and tripes;

A supper was granted - to gain votes for prizes

Whilst the BUTCHERS their bellies and pockets

did rise".

From Sunderland

"All you that does in England dwell,

I will endeavour to please you well;

If you will listen, I will tell

About the cholera morbus.

Please don't be frightened, great or small

The cholera won't come here at all,

If it does it will the Tories call.

It will the cholera morbus. "

From Cheshire

The following was a hit at Lord Delamere, a Tory Peer.

"I would take them (the Poor) into Cheshire and there they

would sow

Both flax and strong hemp for them to hang in a row.

You'd better to hang them and stop soon their breath,

If Your Majesty please, than to starve them to death. "

www.marxists.org/history/erol/uk.secondwave/cpb-gen-1.pdf

'80's saw this timely series of pamphlets. Far off days, where a Nobel Prize for economics would not cause uproar. Maybe even return it out of a sense of decency, after a nosedive in the economy. Clearly the whole subject is far too important to be just left to bourgeois economists.

THE ECONOMICS OF GENOCIDE

Part 1.

AN HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION...

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Aug 15, 2013 7:33:28 GMT

Finance Capital

WORKERS, APR 2011 ISSUE

The history of capital since the Industrial Revolution shows that increasingly it is sucked into the realm of financial speculation. Ever since early manufacturing capitalists had to move beyond self-generation to a stage where they needed to raise more capital to be able to fund their expansion (via the creation of joint-stock companies or closer relationships with banks and financial organisations), then initiative and power started to slip away from manufacturers and was handed over to pre-eminent finance capital.

Finance capital began to view the rate of return of profit from the real industrial economy as both too low and too slow, seeking instead higher and quicker returns from speculative, non-industrial operations. More and more new financial instruments have been designed to absorb this capital. Over time, this flaw in the accumulation process of capitalism produces a baffling contrast: ‘a speculative bubble’ squatting on and suffocating ‘a sluggish real economy’, before eventually it concludes with a spectacular, speculative bust undermining and destroying much of the real economy. We have been subjected to this recently.

Financial instability is an inescapable, inherent part of aged capitalism. As the trend towards satisfying the speculative orgy of finance capital grows within the capital accumulation process, there is even a possibility that the rising mountain and mind-boggling obligation of debt develops so far that it is beyond the capacity of capitalist governments to intervene effectively as “lenders of last resort”. If such a financial avalanche occurs then it will be a catastrophe for capitalism, pulling everyone down with it. We have come close to this nightmare (eg Iceland and Ireland) and it still swirls around in the background but so far these have been absorbed.

The supremacy of finance capital is not a distortion of capitalism, merely an expression of its highest stage of development. When you consider what has happened in the current depression and in previous capitalist depressions, finance capital is now the ultimate fetter on production. Finance capital, which does not produce or contribute anything to society’s wealth creation or well-being, behaves like an unwelcome vampire sucking the life-blood out of the real economy. You cannot factor finance capital out of the equation of capitalism because it is now the controlling entity. So long as you stick with capitalism, then the processes of financial speculation will continue, likely on an ever-deepening scale. We don’t have to wait for the catastrophe to act.

We need to create a society where economic policy advances the real productive economy, where social wealth is generated. In socialist society, banks and financial institutions would exist to re-allocate wealth to industry and social infrastructure. Economic crises and financial instability would become distant, fading memories.

******************************************************************************************8

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Aug 15, 2013 7:48:05 GMT

Absolute Decline

WORKERS, FEBRUARY 2010 ISSUE

Marx analysed 19th-century capitalism as being in decline, never to recover. Many claim this shows Marx was wrong, because capitalism always manages to recover from its frequent crises – so it can go on forever. Yet a longer and deeper overview of history shows Marx was right.

Capitalist forces grew up under feudalism and eventually defeated it, establishing itself as the prevailing economic system. In doing so, it created a new class, of workers who had to work in return for wages. Marx said capitalism created its own gravediggers. So from the time of its greatest triumph, capitalism never again expanded in overall form, and its decline began. Class relationships made this inevitable, and all apparent “recoveries” proved temporary.

In Britain, the working class forced the issue, seeing its own potential power, organising in trade unions to fight the capitalists. Thus it became the dominant force in society – the class which represented the future.

When workers in Russia in 1917 showed they could overthrow the capitalist class altogether and seize and maintain power for themselves, the balance of class forces in the world changed forever. Capitalism’s decline became absolute. From that point, its main aim was to destroy its future assassins – all internal and foreign policies concentrated on bloody war on workers.

This doesn’t seem obvious today. The Soviet Union eventually collapsed (having saved the world from fascism in world war two) together with socialism in China and other countries, and capitalism might seem to have won the class war. Yet the nature of class relationships is the same, and so capitalism remains in absolute decline. It is incapable of offering any kind of growth or progress for the vast majority. It can only destroy.

Now we see an increasingly fast cycle of ever deeper capitalist crises. Capitalism’s major aim is to kill the power of the working class, and decline is deliberately promoted to achieve this end, for example the closure of coal mines in Britain to finish off the miners. By its own actions, it destroys the means of production – industry and agriculture, the banks and the financial system.

Capitalism has no answers to its problems. In absolute decline, it is now exposed in its weakness, but it won’t fall unless the working class strikes it down. We could do it, but we have to want to – this is the challenge.

www.workers.org.uk/thinking/absolute.html

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Sept 6, 2013 15:07:03 GMT

WORKERS, JULY 2009 ISSUE

Transforming nature through labour is the source of all wealth.

Skilled labour combines comprehension with technique. Animals survive mainly through the use of habit and instinct; humans must above all use intelligence and learning. Without the ability to develop the knowledge and practice that is essential to production, humanity would perish.

In pre-industrial times, skill was essential to survival: often quite high level skill, yet survival for many was harsh.

In contrast, modern civilisation depends upon socially organised production, sophisticated technology and high levels of human skill. As an industrial people we are a vast organism of skills and knowledge in which each part is of vital importance to the whole. We have the capacity to create great wealth.

Capitalism despises skill but it cannot do without it. Instead it seeks to restrict it, abuse it, distort it and tailor it purely to make a profit. Hence capitalism’s encouragement of the “free” movement of labour, allowing employers to cherry pick from a rootless, unorganised workforce with no regard to the destructive impact that this has on the skill base of the countries of origin or destination.

Capitalism wishes skill to be instantly available without paying for its development or maintenance. Instead of providing apprenticeships, it prefers to import skilled labour, and is always reluctant to pay a higher rate for skilled labour.

Workers, on the other hand, are for skill, fighting for its recognition, development, and maintenance. We’ve recently seen oil refinery workers take a stand against the deliberate destruction of their skills. The British working class has always fought for its skills. The skilled rate was established and protected through bitter struggle. Our forebears fought for universal education, proper training and apprenticeship. Skill leads to power at the workplace and strengthens class-consciousness.

Skill has moved from being a tool for survival to one of liberation. The industrial revolution unlocked the way to the defeat of misery, ignorance and disease and also the way to the advancement of science and potential abundance. Capitalism now stands in the way.

www.workers.org.uk/thinking/skill.html |

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Sept 17, 2013 8:20:13 GMT

www.workers.org.uk/features/feat_0608/marx.htmlCapitalism isn't working, and workers must find their own solution – or go down with it.

Marx was right!

WORKERS, JUNE 2008 ISSUE

So long as we were able to kid ourselves that capitalism was working, however cruelly, and would see us out, we could avoid the hard intellectual task of trying to understand how it all works. Now it clearly doesn't, so we have to try and do for our time what Marx did for his.

Marx's understanding of capitalism grew from his experience of living and working in Britain, the world's first industrial manufacturing and capitalist economy. Similarly, communists have to understand what is happening now and challenge all the received wisdom – judgement is by results not by proclaimed intentions.

Marx's basic principles still apply. The employer never lets up, even where workers choose to stop resisting. The employer always tries to get more for less – intensification of work – which used to be called "speed-up", and more household members have to work to survive. In the 1930s, there was often just one breadwinner. Now a household needs at least two workers to keep going, and increasingly the next generation lives at home, trying to find work or working for nothing or for a pittance. Household debts, just like local authority debts, company debts, government debts and trade deficits, keep growing.

Mass immigration means they have no need to reproduce labour power here – no need for a home-grown British working class. They'd let our class rot and import another one already educated and keen to work for less. The government maintains the EU's dogma of unrestrained immigration, whatever the consequences, whether we like it or not. The government talks of a future population of 70 million – is this what we want? And if immigration is not controlled, the number could be 80 million or 100 million. Is there really no sensible limit? And even this device for increasing profits has not prevented the crisis we see today.

Take responsibility

We must take responsibility for our land and for the size of our population. If we don't care for our land and our people, who will? The days of Empire, when we could migrate into other peoples' countries without their consent, are over.

Is manufacturing really the wealth-producing base, or can finance capital save us, as Thatcher, Blair, Livingstone and now Brown propose? Why has London become once more the financial capital of the world? Where does Canary Wharf come from? Are we already in a "post-industrial" world, as so many parrot? Surely, if there were no industry at all, we could not still be alive. If we were producing no goods, how could we continue to consume?

Unite pickets at Ineos in April: they showed that workers can win –

and that capital never accumulates enough profit for the capitalists

Photo: Workers

They tell us that property is the way to escape debt and dependency. But Inside Track, the biggest buy-to-let company, crashed in April. It spearheaded the buy-to-let scam, promising to show customers "how you could give up work and be a property millionaire instead". Now buy-to-let mortgages dry up as British new-build flats, Spanish apartments and Florida homes all lose value, Spanish apartments by 30 per cent. Housing starts in Britain fell by a quarter between January and March this year. As Workers has said, "Financial services – not so much an industry, more a short-cut to debt and dependency'" The drive for profit by those parts of the capitalist class who own and control the finance companies is responsible for that debt and dependency, urged on by the successive governments who serve them.

We are told that there is a "credit crunch" because of the US housing sub-prime market collapse. Workers in September 2007 called capitalism itself "A sub-prime system". Sub-prime means banks parcelling up bad debts with good. But this is nothing new. In the early 1990s, the IMF's Brady Plan repackaged developing countries' debts as collateralised tradeable bonds, privatising debt ownership, so venture (vulture, hedge fund) capitalists could buy debts and then sue for full, immediate repayment.

For example, in 1996 a company called Elliott Associates bought from the IMF $20 million of Peru's debt for $11 million; it then sued Peru's government and won $58 million, a cool $47 million profit. They have pulled the same trick in Panama, Poland, Turkmenistan, Ecuador, Ivory Coast and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Debt rescheduling means capital bondage. The peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America pay $5 in debt repayment for every dollar of aid their governments receive. Under finance capital's rule, one billion people only get a dollar a day, whereas every cow in the EU gets $2 in subsidies. For every $1 the US taxpayer gives to the international financial institutions, US companies get $2 in bank-financed procurement contracts. For every $1 going into developing countries (investment, aid, grants), $2 come out to service debts. Since the mid-1960s, $22 billion a year has gone from the developing countries to the capitalist classes in the USA and the EU.

The capitalist classes designed the World Bank and the IMF to benefit themselves and to harm the working class, to defeat economic rivals, like East Asia's developing states, to try to destroy Russia and flatten Africa. Capitalism's regional Free Trade Agreements, like the EU's, threaten state sovereignty, workers' rights, local cultures, and render meaningless all forms of democracy and representative government since decisions are actually being made elsewhere.

The government tells us three million British jobs depend on the EU, because they produce the goods we export to the EU. But there is another side to the story. Our imports from the EU are 21% more than our exports. (In 2007 our trade deficit with the EU was a record £40 billion.) So if the exports create three million jobs, then the imports must be destroying 3.6 million jobs. So we make a net loss from the EU of 600,000 British jobs.

EU rule

This EU rule is not legitimate. We have not consented to it, either by majority participation in EU elections, or by participating in drafting the EU Constitution, or by freely ratifying that Constitution. The Constitution has neither the explicit nor even the tacit consent of the majority of British citizens, so the government acted illegitimately when it ratified the Constitution.

The government's arguments against holding a referendum on the Constitution are arguments against democracy. To refuse a referendum on the issue of increasing EU integration, on which all the parliamentary parties promised a referendum, is to attack democracy. The government opposes a referendum because it fears and opposes the people. We are for real democracy not for parliamentary democracy, where, in theory, the people rule, but then the state overrules and does what the capitalist minority wants.

We said the bubble would burst, and now it has. And they mean for workers to pay. The government says the answer is to squeeze public sector pay, 2.5 per cent rises for the next five years, when inflation, even on official figures, is 4 per cent and rising. People are voting against increasing exploitation, lower wages, rising living costs, Post Office closures, and the attack on pensions, against government arrogance, dishonesty, corruption, spin and denial of reality. People vote against one lot of rascals or the other, usually to get shot of the rascals in office when their corruption becomes intolerable. But it is not enough just to kick the rascals out every five, ten or fifteen years.

We workers have to find a way ourselves to run and rebuild Britain or else capitalism will pull us down with itself, starve us out and hope to find someone else to exploit. We have to find a way, and it starts with class thinking and struggle.

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Sept 17, 2013 14:08:20 GMT

Fine survey of the second great depression and what we must do to end it, 16 Sep 2013

This William Podmore review is from: Global Capitalist Crisis and the Second Great Depression: Egalitarian Systemic Models for Change (Paperback)

US economics professor Armando Navarro has written a very useful book on the present crisis and on how to end it.

He points out that the USA's second great depression is due to a failed capitalist system in absolute decline. The incessant global capitalist crisis created the depression. The US subprime mortgage crisis in 2006 was the trigger for the 2007 world financial crisis, the 2008 world economic crisis, and the 2009 depression.

One billion people are undernourished. Half the world's people live in poverty, a quarter live in extreme poverty. A billion children, half the world's children, live in poverty. Since 1970, 300 million people have died of starvation and curable diseases.

Navarro remarks that Obama's welfare capitalist policies of 2009-10 are like the New Deal, which stabilised the first Great Depression, but did not relieve it. Capitalism is still exploitative and predatory.

Navarro notes all the false claims of recovery, and points out that the US and British economies are experiencing a massive grouping of bubbles, in the housing, assets and commodities markets.

Navarro proposes models for change towards a more equal society. He asserts that the working class movement in every country must have a democratic centralist cadre party, organised and disciplined, with a coherent ideology and an experienced body of leaders. He gives the Bolshevik Party as an outstanding example.

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Sept 20, 2013 13:56:16 GMT

imarxman.wordpress.com/2011/03/23/king-arthur-and-the-labour-theory-of-value/King Arthur and the Labour Theory of Value

Posted on March 23, 2011 by imarxman

Once upon a romantic day Sir Ector made his way to a tournament accompanying his son, Sir Kay and his ward Arthur. Calamity! Sir Kay, a careless young knight, realised he’s forgotten his sword and the jousting was about to begin. Arthur, acting as Kay’s squire, rode off in search of a suitable weapon, conveniently finding one apparently abandoned in a local churchyard. True the blade has been driven half its length into the middle of an anvil securely fixed on top of a great rock. Not knowing many a knight has already proven himself too feeble to extract the sword from this eccentric fixing, Arthur leapt up onto the stone and with little effort plucked the sword free. The rest, as the cliché runs, is history.

Except, of course, it is not history. Or is it? Set aside the soft focus romance and the idealism of an age of perfect chivalry and examine the material components of the story instead. The essential elements, in ascending order, are the rock, the anvil and the sword. Now consider Arthur, not as a medieval template of perfect Christian kingship or even as a 6th Century Celtic warrior leading his tribe against insurgent Saxons. Rather an Arthur whose power arises from a magical ability, a man who can work metal.

Arthur, the protégé of Merlin, personifies what once was a mysterious practice, iron production. What is now taken for granted as a common industrial process was regarded as having supernatural overtones. Having made Sirs Ector and Kay redundant and incorporating Merlin as representing secret knowledge only revealed to a few, an Arthur emerges who can do wonderful things.

Firstly, he takes the rock, or iron ore as it known today, and heats it until the metal it contains becomes molten and flows out. Once this smelting has taken place, the resulting brittle iron is heated and reheated by Arthur who repeatedly hammers the red-hot ingot on his anvil, driving out the impurities. Maybe he introduces a little carbon to transform the emerging wrought iron into steel. This continues to be shaped on the anvil into a blade that can be honed on a whetstone. Arthur has drawn the sword from the stone.

In doing so he has created not only a fine weapon, but something the sword has in common with everything that’s ever been made through human agency however grand or mundane: value. At every stage of the process value is added. The iron ore has no value to humanity while it remains undisturbed rock, but along comes the miner who extracts it from the earth and that lump of stone has acquired value; it can be sold. Arthur, acting as the personification of all metalworkers, then goes through each of the subsequent stages. Smelted, cast, wrought, made into steel, pommel and hand guard fashioned, grip affixed to the hilt, blade honed keen and polished; each stage adds to the value of the finished implement. Which is why common foot soldiers of those days were armed with spears, being cheaper to make than swords requiring much more work in their manufacture.

And it is work that is the crucial element, labour measured by time. Two types of labour actually, direct and indirect. The direct labour was the work required by Arthur to properly complete each part of the process by which he drew the iron from the stone and fashioned it into a sword. There was also his indirect labour, that is the previous years of apprenticeship spent learning and developing the skills required to successfully work iron. There was also the miners’ labour-time and that of the charcoal burners who produced the purer fuel from wood required for smelting. All that labour accumulated as the value of the finished sword demonstrating, even in dark ages, the importance of the light Marx shone to illuminate the universal source of value.

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Sept 30, 2013 7:15:32 GMT

Monopoly - 13 firms at capitalism's core

WORKERS, OCT 2013 ISSUE>

A study by academics Peter Phillips and Brady Osborne, part of the soon-to-be-published Project Censored 2014, reveals just how far the global concentration of capital has advanced.

The two researchers have analysed the top ten asset management companies and the top ten most centralised corporations in the world, identifying between them just thirteen firms, with 161 directors, that dominate the financial core of capitalism worldwide. These firms collectively control funds worth $23.91 trillion – roughly ten times Britain’s entire annual GDP.

The analysis goes further, presenting a history and analysis of wealth, the individuals and the companies, the relationship to the US military and NATO as their effective enforcers worldwide. More detailed studies of the US economy show that the 2.5 per cent most wealthy US citizens increased their wealth by 75 per cent between 1983 and 2009, while 80 per cent of US households saw their income reduce.

In practical terms that equates to the top 1 per cent having an average household wealth of $14 million dollars, while 47 per cent of the US population have an average household wealth of zero dollars.

Project Censored 2014: Fearless Speech in Fateful Times, Project Censored, will be available at projectcentral.org/store, $19.95.

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Oct 16, 2013 21:25:23 GMT

Excellent survey of finance capital's successes and failures, 16 Oct 2013

This Will Podmore review is from: Stiglitz Report, The (Paperback)

In 2008, the President of the UN General Assembly, Miguel d'Escoto Brockmann, convened an international committee of 20 financial experts, chaired by Joseph Stiglitz, to address the crisis and its impact on development. This is valuable because the General Assembly, the one inclusive international body, is far more democratic and representative than the G20 or the G8.

The Commission forecast, "those who have benefited from existing arrangements will resist fundamental reforms." As Stiglitz notes in his January 2010 preface, "In most countries, the financial sector has successfully beaten back attempts at key regulatory and institutional reforms. The financial sector is more concentrated; the problems of moral hazard are worse. Global imbalances remain unabated." Many financial institutions are still `too big to fail'. As the Commission observes, "In many countries, the financial system had grown too large; it had ceased to be a means to an end and had become an end in itself."

The Commission remarks, "At the global level, some international institutions continue to recommend policies, such as financial sector deregulation and capital market liberalization, that are now recognized as having contributed to the creation and rapid diffusion of the crisis."

Too many governments are still wedded to market fundamentalism, even though "cutbacks in investments in infrastructure, education, and technology will slow growth." As the Commission points out, "the EU is imposing pro-cyclical policies on the enlargement countries, including wage and expenditure reductions in the public sector."

The Commission notes that the present system of flexible exchange rates "has proven to be unstable, incompatible with global full employment, and inequitable." "Developing countries are, in effect, lending to developed countries large amounts at low interest rates - $3.7 trillion in 2007" - far more than the aid they get back.

It observes, "in some countries, there has been excessive focus on saving bankers, bank shareholders, and bondholders instead of on protecting taxpayers and greater focus on saving financial institutions than on resuming credit flows." This has caused "a massive redistribution of wealth from ordinary taxpayers to those bailed out."

As the Commission notes, "Unregulated market forces have provided incentives not only for under-production of innovative financial products that support social goals but also for the creation of an abundance of financial products with little relevance to meeting social goals." But regulation is not a sufficient remedy. As the Commission points out, "The incentives faced by public officials, regulators, and elected officials, and the role of money in politics are important antidotes to romantic notions of the efficacy of regulation to correct for market failures."

The Commission rejects market fundamentalism, that the market is the solution to every problem, rather than the problem to every solution. Yet the Commission itself is still in thrall to all too many market dogmas. For example, it writes, "Had the financial sector in richer countries, such as the U.S., performed their critical function of allocating the ample supply of low cost funds to productive uses, the world economy might now be facing a boom rather than today's economic crisis." No, financial firms' `critical function' is to maximise their shareholders' profits, not to steer investment into production.

Again, the Commission refers to `the pervasive and persistent failure of financial institutions', and to `market imperfections' and `market failures'. But the market worked: it made shareholders richer, as it is designed solely to do, so it succeeded.

The Commission points out that "in financial markets, private incentives, both at the level of the organization and the individual decision-maker, are often not aligned with social returns." Why should private incentives be `aligned with social returns'? The market does not exist to serve society but to maximise private profit, whatever the social effects.

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Oct 30, 2013 2:08:02 GMT

www.workers.org.uk/thinking/production.htmlContinuing our series on aspects of Marxist thinking

Production for Use

WORKERS, NOV 2012 ISSUE Human beings have always had an insatiable desire to make objects that make life easier, more tolerable or more fulfilling. Today, such products are presented in the form of commodities and exchanged via capitalist markets. As we have become used to markets, we can easily delude ourselves into imagining that things have always been arranged as they are now.

Yet, in the past, things were different. The impulse to produce things stemmed mostly from the need to satisfy immediate wants. Objects were manufactured because they were necessary, useful or pleasant. They had a use value, goods being normally intended for family or tribe. And barter developed for goods you weren’t able to make yourself but wished to have. Though the chief reason for manufacture in early human society was to enhance prospects of survival by producing vital items such as clothing, tools, cooking utensils and weapons, a delight in crafting decorative items always coexisted.

Over millennia production for exchange emerged, grew, and gradually swept aside the overriding concern of production for use. Increasingly, goods assumed a different character, as commodities for sale and exchange on the market. But the rise of capitalism brought a marked change. Labour itself was made into a commodity, and the process of commodity exchange interwove itself as the exploitative link connecting the whole system of capitalism.

While workers invest their labour producing an object, it remains the employer’s personal property; the object has been turned into merchandise. The purpose of production for capitalists is never the use value of the objects made but their potential exchange value, in which surplus value and profit are created.

Though production of use values is a natural condition of human existence and constitutes the true substance of wealth creation, capitalism sabotages this and turns everything into a commodity – if we let it. Nowadays it is not only manufactured products that are commoditised but also essential infrastructure and services on which we depend: railways, transport, power generation, education and health (even the prospect of prisons and policing) are transformed into commodities, into desperate opportunities for the generation of exchange value and profit, rather than kept as use values vital for the smooth running of greater society.

Even worse, finance capitalism seems happy not to make or provide anything, content to commoditise money and debt and endlessly speculate, a foolhardy approach that ends in bubbles and crashes.

Despite its apparent supremacy, production for exchange will not last forever and will eventually be consigned to the museum of memory. Production for use, however, is unlikely to happen without a fight. Those in whose interest the current system operates can be expected to resist the introduction of a society of workers, combining together to produce an abundance of goods necessary to ensure all needs are fully met.

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Nov 1, 2013 6:02:58 GMT

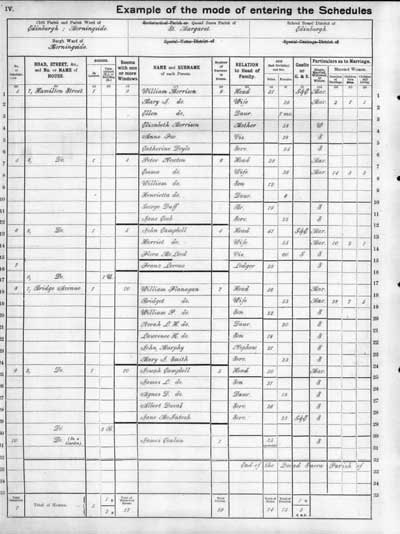

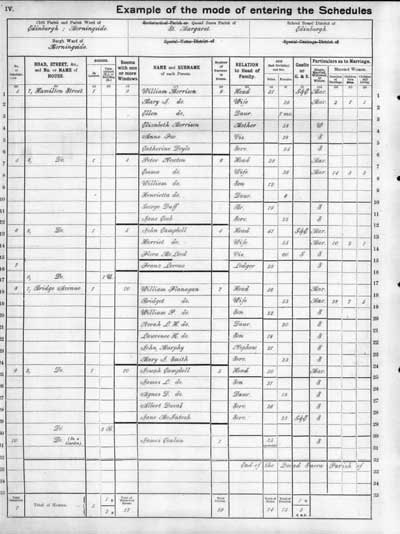

After more than two centuries, capitalism has decided it doesn’t really need to know what’s going on in Britain – and that the census should go...

Who's counting? Not the government...

WORKERS, NOV 2013 ISSUE Extract from the 1901 census (Edinburgh)In 1801 Britain held its first census. At that time, as an industrial nation emerged, there was an understanding that the country needed to know how many mouths it had to feed, what the workforce might be, how many people might be available for the armed forces, and so on.More than 200 years later, capitalism has decided it no longer needs to know such things. In a consultation put out by Francis Maude, one of the last survivors from the Thatcher cabinets, it proposes instead online surveys and the use of other existing government-collected data.The trained enumerators who went from house to house for each census will be replaced by SurveyMonkey. Though the cost of the census is cited as the reason, in reality, as ever, it is not about money. The Financial Times estimates the entire Office for National Statistics budget for the current financial year is about 0.03 per cent of total public spending – or about 6p a person per week.Since the latter half of the 20th century the collection of data has never been important to government. Thatcher’s Rayner Review cut statistical services by a quarter, while in 2006 the Blair government moved the Office from London to Newport in south Wales, losing many experienced staff in the process. Yet the 2011 census showed that there were almost half a million more people living in Britain than estimates based on other data sources had suggested. Our ability to understand, as a nation, who lives here, and who has come here from abroad, is at stake.Statisticians consider the census as a way of linking up the information obtained from many other sources to provide small-area statistics which enable the planning of education, healthcare, public transport, etc. So if the census were to be abandoned, our ability to understand health inequalities, for example, would suffer. We would not know how many bedrooms there are, nor how many people occupy them, how many graduates are available for employment in a particular part of the country, and so on.Presumably the capitalists and their politicians today consider that population and public services – like everything else – can be left to the “Market”, so really what need is there for planning based on the needs of the population?Cancellation of the 2011 census was seriously considered when the coalition government crept into power in 2010, but plans were too far advanced. The last time a census was cancelled was in 1941, when we were at war with fascism. Information from the previous 1931 census provided support for many of the gains won in the peace, the NHS and education. Will the dictatorship of finance capital we now live under be permitted to stop the next one? Extract from the 1901 census (Edinburgh)In 1801 Britain held its first census. At that time, as an industrial nation emerged, there was an understanding that the country needed to know how many mouths it had to feed, what the workforce might be, how many people might be available for the armed forces, and so on.More than 200 years later, capitalism has decided it no longer needs to know such things. In a consultation put out by Francis Maude, one of the last survivors from the Thatcher cabinets, it proposes instead online surveys and the use of other existing government-collected data.The trained enumerators who went from house to house for each census will be replaced by SurveyMonkey. Though the cost of the census is cited as the reason, in reality, as ever, it is not about money. The Financial Times estimates the entire Office for National Statistics budget for the current financial year is about 0.03 per cent of total public spending – or about 6p a person per week.Since the latter half of the 20th century the collection of data has never been important to government. Thatcher’s Rayner Review cut statistical services by a quarter, while in 2006 the Blair government moved the Office from London to Newport in south Wales, losing many experienced staff in the process. Yet the 2011 census showed that there were almost half a million more people living in Britain than estimates based on other data sources had suggested. Our ability to understand, as a nation, who lives here, and who has come here from abroad, is at stake.Statisticians consider the census as a way of linking up the information obtained from many other sources to provide small-area statistics which enable the planning of education, healthcare, public transport, etc. So if the census were to be abandoned, our ability to understand health inequalities, for example, would suffer. We would not know how many bedrooms there are, nor how many people occupy them, how many graduates are available for employment in a particular part of the country, and so on.Presumably the capitalists and their politicians today consider that population and public services – like everything else – can be left to the “Market”, so really what need is there for planning based on the needs of the population?Cancellation of the 2011 census was seriously considered when the coalition government crept into power in 2010, but plans were too far advanced. The last time a census was cancelled was in 1941, when we were at war with fascism. Information from the previous 1931 census provided support for many of the gains won in the peace, the NHS and education. Will the dictatorship of finance capital we now live under be permitted to stop the next one?

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Nov 5, 2013 5:55:27 GMT

A remarkable survey of the industrial origins of wealth, 8 Sep 2009

This Will Podmore review is from: Wealth And Poverty Of Nations (Paperback)

This remarkable book asks why some nations are wealthy and others poor, why some nations developed industry and others didn't.

Spain and Portugal, for example, gained capital from empire but wasted it on luxury and war. Their belief was that did not have to make things any more because they could buy them. Landes cites a Spaniard: "Madrid is the queen of Parliaments, for all the world serves her and she serves nobody." Landes comments, "Such foolishness is still heard today in the guise of comparative advantage and neoclassical trade theory. I have heard serious scholars say that the United States need not worry about its huge trade deficit with Japan."

When Britain's governments and economists tried to persuade others to adopt free trade, "most other countries saw this as a device to keep them in their agricultural place." Banker David Ricardo, for example, wrote of the virtues of `comparative advantage', which leads in practice to specialisation, when countries need instead to diversify their economies to develop. The theory served only Britain's advantage, because it backed her policy of keeping poorer countries down as producers of raw materials.

Landes observes, "Portugal was Ricardo's chosen example of the gains from trade and pursuit of comparative advantage." In fact Portugal's comparative advantage in producing port and sherry led to its failure to develop its agriculture and industry and made it a colony of Britain.

Again, "If the Germans had listened to John Bowring ... That British economic traveller extraordinary lamented that the foolish Germans wanted to make iron and steel instead of sticking to wheat and rye and buying their manufactures from Britain. Had they heeded him, they would have pleased the economists and replaced Portugal, with its wine, cork, and olive oil, as the very model of a rational economy. They would also have ended up a lot poorer."

It wasn't just theory: "The nineteenth century saw Britain protect the Ottoman empire from the territorial ambitions of its adversaries, while blithely killing off its manufactures." As it did with Ireland and India. Landes sums up, "history's strongest advocates of free trade - Victorian Britain, post-World War II United States - were strongly protectionist during their own growing stage. Don't do as I did; do as I can afford to do now."

He writes, "It is no accident that much of the literature on dependency has been the work of Latin American economists and political scientists. They feel, with some justice, that their part of the world, though nominally free, has been put down and looted by stronger partners." He admits that they have a point, "maybe that was the first priority: freedom first, economy later; because freedom is a necessary if not sufficient condition of development."

He has a brilliant discussion of the Industrial Revolution (1770-1870), asking why it started in Britain. It was partly because we made early starts in fossil fuel, agriculture, transport, textiles, iron and steel. As he notes, "Britain had the makings; but then Britain made itself."

"Wealth is not so good as work. ... what counts is work, thrift, honesty, patience, tenacity." Finally, he observes, "Britain had the early advantage of being a nation ... Britain, moreover, was not just any nation. This was a precociously modern, industrial nation."

|

|