|

|

Post by dodger on Aug 7, 2013 10:12:56 GMT

Chainmakers – Breaking Their Chains

www.theworker.org.uk/blog/?p=808

Jul

09

2013

The first Saturday in June has become an annual celebration in recognition of the Cradley Heath Women Chainmakers strike. This event is probably the largest celebration of women’s industrial history in Britain.

The festival celebrates the achievements of 800 women Chainmakers who fought to establish a minimum wage for their labour in 1910 by striking for ten weeks. They were the first workers ever to establish a minimum wage.

The Black Country and Cradley Heath area became the centre for chain making – a ‘sweated’ trade – in Britain in the 19th century. Men in factories produced heavy to medium chains. The smaller hand hammered chains were made by women and children in small dark forges in outbuildings next to the home.

Poverty wages were the norm. After a campaign by the anti-sweating league, the Liberal government passed the Trade Boards Act in 1909 to set up regulatory boards to establish and enforce minimum rates of pay for workers in four sweated trades.

In the spring of 1910, the Chain Trade Board announced a minimum wage for hand-hammered chain-workers of two and a half pence an hour which for many women was nearly double the existing rate. At the end of the Trade Board’s consultation period in August 1910, many employers refused to pay the increase.

In response, the women’s union, the National Federation of Women Workers (NFWW), called a strike. The strike attracted immense popular support from all sections of society. Within a month 60% of employers had agreed to pay the minimum rate and by the 22nd October the last employer signed the list.

This was a huge victory – one that fed the mood for an escalation of strikes before the First World War, known as the Great Unrest. By the time those years of struggle were over, the size of Britain’s trade union movement had doubled from two million members to four million.

The Chainmakers festival has been running for 10 years now and it is important to recognise the importance of the dispute and role the women played in shaping industrial struggle. It is vital that this festival receives increased national support and recognition from trade union leadership in the future. Many of the lessons learned in running the dispute successfully just over 100 years ago are still relevant today.

Further reading: Tony Barnsley: Breaking Their Chains

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Aug 11, 2013 17:40:59 GMT

first thoughts: slavish thinking

WORKERS, DECEMBER 2002 ISSUE

AT A RECENT conference in the Caribbean, Cuba denounced as "racist" the demand that only non-white delegates could discuss slavery and reparations to their descendants. Those who called for the exclusion of non-black delegates were from the largest delegation present – from Britain.

At the same time the US city of Chicago deemed that any company wishing to tender for work must be able to demonstrate that they never profited, owned or traded in slaves. How pious.

Slavery throughout history has been about the brutalisation of economic relations between people. Skin colour is but one aspect – one that is ignored by those who still perpetuate this barbarity in Africa to this day. Slave owning societies were replaced by wage-slave societies. Slavery in the USA was abolished 140 years ago, but the working class of the Americas – north and south hemispheres – still faces abject wage slavery.

The key to slavery is class, not race, whether the slaves are Britons resisting the Roman Empire or Irish deported to the Caribbean in the 17th century, or Jews and Soviet citizens in Nazi Europe or the millions drawn to the Tiger economies of the Pacific Rim.

The unravelling of the human genome last year has damned those who would divide humanity into so-called "races" to the dustbin of history – there is more genetic variation within ethnic groups than there is between them. So there is but one human race, and it is divided by class, not colour.

The nonsense of the perpetual victim guilt trip of those who would seek reparations as a remedy to the evils of the world would trap us into having to put up with those evils forever. We are not to be mesmerised by slavery, starvation, ignorance, homelessness, ill health, inequality, discrimination, denial of human dignity.

We are not going to grovel at past events and shriek and wear sackcloth and ashes for past wrongs. The brutality imposed on populations of the world stems from the economic system of capitalism. Permanently ending that system is the only way to hush the ghosts of past inhumanity and the only way to prevent future repetition.

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Aug 11, 2013 17:51:01 GMT

back to front: help yourself

WORKERS, MARCH 2003 ISSUE

IN THE 20 years since the identification of the HIV virus, the AIDS epidemic has ravaged sub-Saharan Africa, where in many countries it is the major cause of adult death. AIDS is a massive problem almost everywhere in the world (including now in China), a challenge to public health and to science.

The pharmaceutical companies love a major disease. Let’s face it, without disease they would be out of business. So the onslaught of AIDS brought with it R&D programmes as the companies raced to find first diagnostic tests, then drugs to treat AIDS.

It is a tribute to human ingenuity that a range of drugs have been produced that, between them, have the ability to markedly extend the life expectancy of people with HIV. There is no cure, but people are living far longer – that is, if they have access to the drugs.

But the cost of drugs is only one aspect of human health. And last month, the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Denver, Colorado, heard about the other aspects.

In front of an audience composed mainly of scientists, Dr Byron Barksdale from the American Cuban Aids Project explained how Cuba, alone among the so-called "developing countries", had contained and reduced the spread of HIV through concerted public health measures allied to modern drugs.

It came as a surprise, apparently, that little Cuba had itself developed three antiviral drugs which it used in the fight against AIDS. In fact, Cuba decided many years ago that it had to develop its own pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries – either that, or be at the mercy of foreign multinationals.

Instead of complaining that capitalists were acting in their class interest, Cuba’s workers decided to act in their own class interest. As a result, Cuba has one of the lowest levels of AIDS in the world. Mortality is 7% instead of the "expected" 25%; and transmission from infected needles, from blood transfusions or from mother to child is virtually unknown.

Oddly enough, this, the exercise of workers’ power through socialism, is seen as "utopian" by many.

Yet the same people who call Marxists "utopian" seem quite happy to embark on a propaganda war in an attempt to convince pharmaceutical companies to start behaving as charities. It is as though the inhabitants of Hell passed a resolution calling on the Devil to turn down the flames – poignant, but hardly powerful. When workers fail to take responsibility for their own futures, why should they be surprised that capitalists refuse to take responsibility for what happens to workers?

There is a solution to bad health, greedy drugs companies and venal governments, and it has been available to workers throughout the world ever since the Russian Revolution of 1917, no less so to the working people of Africa or Britain than those in Cuba. Take charge, take control. Don’t call for aid, help yourself.

top

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Aug 11, 2013 19:24:56 GMT

Wilberforce's opposition to the slave trade was founded on the same basis as his hatred of trade unions, free speech, habeas corpus and universal suffrage: the interests of capitalism...

William Wilberforce: enemy of the working class

WORKERS, JULY 2007 ISSUE

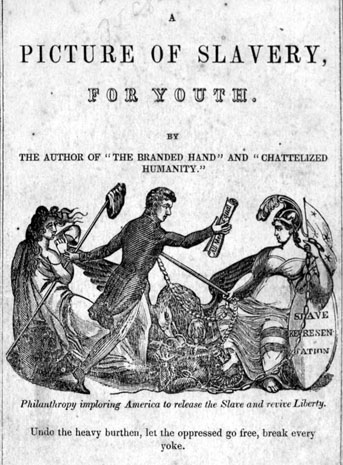

Far too much credit for the abolition of slavery is given to William Wilberforce, one of history's biggest hypocrites and reactionaries. It was only by their own action that the slaves were freed.

During the 18th century, Britain became the slave carrier for the sugar planters of France and Spain, her rivals. The sugar colonies were far more important to France than to Britain. St Domingue (present-day Haiti), controlled by the French, was more fertile than the British West Indies (which included Jamaica), where the soil was becoming exhausted. The sugar from St. Domingue cost a fifth less and its exports and profit rates were twice that of Jamaica. By 1789, its sugar production was a third more than that of all Britain's West Indies colonies.

Prime Minister William Pitt raged that the slave trade, "instead of being very advantageous to Great Britain, is the most destructive that can well be imagined to her interests." To ruin St Domingue, he urged his friend William Wilberforce to campaign against the slave trade: the abolitionist movement was created to serve British state interests.

The British ruling class's frenzied reaction to the French revolution of 1789 intensified the antagonism with France, as she became not just a rival but also a political alternative. In 1791, St Domingue's slave-owners offered to leave French rule and put themselves under British rule, to keep their slaves. In 1793, Pitt accepted their offer and agreed, blocking abolition for the next 14 years.

When St Domingue's slaves rebelled against Pitt's betrayal, he sent hundreds of thousands of troops to try to crush them, in a disastrous and futile war. 50,000 British soldiers died, 50,000 were permanently invalided. When St Domingue's revolutionary government ended slavery and declared independence from France in 1804, the British ruling class did not need the slave trade any more and so could abolish it in 1807.

Tolpuddle Rally

Tolpuddle: time for a rally against Wilberforce? He piloted through Parliament the anti-union Combination Acts, which made all unions illegal.

Reactionary in Britain

In Britain, Wilberforce was the foremost apologist and champion of every act of tyranny, from the employment of Oliver the Spy and the illegal detention of poor prisoners in Coldbaths Fields jail to the Peterloo massacre. Wilberforce supported the 1794 Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, which let the government imprison people against whom it had no evidence at all. Habeas Corpus was suspended until 1802. Across Britain, trade union members, journalists and publishers were arrested and detained.

Wilberforce backed a series of Acts between 1795 and 1799 to suppress sedition, used to curb freedom of speech, assembly and organisation. Consequently, the state prevented meetings of the Literary Society of Manchester, the Academical Society of Oxford, and even of a mineralogical society, on the grounds that the study of mineralogy could lead to atheism. He backed the Tory government's Six Acts of 1819, including the Blasphemous and Seditious Libel Act, known as the Gagging Act.

In 1794 he backed the prosecution of twelve members of the London Corresponding Society for high treason. Their crime was to advocate universal suffrage. When a jury acquitted the defendants, he backed the government's decision to arrest 65 leading members of the society and imprison them without trial for two years. No wonder that it was said of Wilberforce, "he never favoured the liberty of any white man in all his life."

Wilberforce wrote that Christianity "renders the inequalities of the social scale less galling to the lower orders, whom also she instructs in their turn to be diligent, humble, patient: reminding them that their more lowly path has been allotted to them by the hand of God; that it is their part faithfully to discharge its duties, and contentedly to bear its inconveniences." William Cobbett called him the prince of hypocrites, who praised the benefits of poverty from a comfortable distance.

The bishops and baronets of the Proclamation Society (as Wilberforce's Society for the Suppression of Vice was earlier called) prosecuted the impoverished publisher of Tom Paine's The Age of Reason. In 1801 and 1802, it launched 623 successful prosecutions for breaking the Sabbath laws. Pitt's government declared The Rights of Man seditious and prosecuted those who published and sold copies of Paine's book.

Censorship

The government, with Wilberforce's support, imposed censorship, launching 42 prosecutions of publishers, editors and writers between 1809 and 1812. It became a criminal offence to write that the Prince of Wales was fat (he was), or to report that Foreign Secretary Lord Castlereagh had ordered the flogging of Irish peasants (he had).

Wilberforce also backed persecution of the whole working class. He proposed a general Combination Act, calling combinations – trade unions – "a general disease in our society". The Pitt government's acts of 1799 and 1800 were the severest of their kind ever enacted in Britain. They made all unions illegal as such, whether conspiracy, restraint of trade or the like could be proved against them or not.

In theory, the acts applied to employers as well as to workers, but workers were prosecuted by the thousand, never a single employer. In 1834, a year after the emancipation of the slaves, the penalty for trade union activity was still transportation for life.

In sum, as his biographer the last Lord Birkenhead wrote approvingly, Wilberforce "was a Tory through and through; he never shed the political ideas he had inherited from Pitt and his religion intensified his conservatism."www.workers.org.uk/features/feat_0707/wilberforce.html

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Aug 17, 2013 8:20:00 GMT

www.workers.org.uk/features/feat_0507/abolition.htmlThe British Empire, still so often praised for its shaping of world history over the last few centuries, was at root a slave empire...

Abolition? What abolition?

WORKERS, MAY 2007 ISSUE

The British Empire, still so often praised for its shaping of world history over the last few centuries, was at root a slave empire, held together by slave-trading between slave colonies, a world system mirroring only more grotesquely its domestic system of wage slavery. Between 1660 and 1807, British-owned ships carried 3.5 million Africans, 40,000 a year, across the Atlantic – more than any other country. British property owners were the world's chief slavers.

A part of Britain's ruling class, not the nation, owned the slave ships, the slaves and the plantations. British workers did not control their own labour power, never mind own other people. William Cobbett noted that in 1832, "white men are sold, by the week and the month all over England. Do you call such men free, on account of the colour of their skin?" Black chattel slavery and white wage slavery were parts of the same system.

Fine words, but the truth is that abolition began to serve the employers better than slavery.

Wage slaves at home

By the 19th century the more powerful part of Britain's ruling class were those who exploited wage slaves at home. They led the abolitionist movement, ignoring the eighteen-hour days worked by children in Bradford's mills. They backed the laws that attacked trade unions and suspended Habeas Corpus. They funded their foreign philanthropy by increasing the exploitation of their white slaves at home. The trade unionist Oates said, "The great emancipators of negro slaves were the great drivers of white slaves. The reason was obvious. The labour of the black slaves was the property of others. The labour of the white slaves they considered their own." As the Derbyshire Courier noted, "We make laws to provide protection to the Negro: let us not be less just to the children of England."

Bronterre O'Brien wrote, "What are called the working classes are the slave populations of the civilized countries." From birth, workers were mortgaged to the owners of capital and land, forced into wage slavery. Britain's property owners gained far more profit from their 16 million wage slaves than from their million chattel slaves. O'Brien again, "We pronounce there to be more slavery in England than in the West Indies ... because there is more unrequited labour in England."

slavery

Fine words, but the truth is that abolition began to serve the employers better than slavery. The empire was based on exploiting wage slaves and used the free movement of goods, capital and labour to extend its exploitation. The wars of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries were fought to keep, or add to, Britain's imperial and slave-trading conquests. For example, in the 1790s, British slave owners united with French slave owners to try to defeat Haiti's revolution. The government sent more soldiers to the West Indies, and lost more, than it had when trying to crush America's independence. Of the 89,000 sent, 45,000 died, as did 19,000 sailors. France lost 50,000 dead. Haiti's freed slaves defeated the armies of the two greatest slaver powers, but the British forces laid waste to the island, destroying almost all its sugar plantations.

By 1807 the slave trade was becoming less profitable: it employed only one in 24 of Liverpool's trading ships and the West Indies sugar industry was dying. All the plantations were running at a loss; many had been abandoned. Two-thirds of the slaves carried in British ships were bought by Britain's imperial rivals France and Spain, to grow sugar which undercut West Indies-grown sugar on the vital Continental market. All these factors opened the way to the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act; from 1 May 1807, no more slave ships sailed from Britain.

But the government let the British Army and the Royal Navy force slaves into unpaid military service and buy and sell slaves until 1812, breaking its own law. The office of Jamaica's Governor General wrote in August 1811, "I am commanded by the Commander of the Forces to direct that you will go on purchasing Negroes for the Kings Service after you have completed your own regiment. The men so purchased are only to receive rations and slop clothing, no pay is to be issued to them until they are further disposed of."

Further, in 1814, Foreign Secretary Lord Castlereagh agreed that Bourbon France could resume slave trading to restock her colonies and to resupply Britain's West Indies plantations. As Lord Grenville said, "We receive a partial contract at the Congress of Vienna by which the British Crown has sanctioned and guaranteed the slave trade."

Slavery lost its former importance to the metropolitan economy. The slave colonies took an ever-smaller share of Britain's exports. From 1820 the slump in the West Indies grew worse and worse. In 1832, an official wrote that the West Indies system "is becoming so unprofitable when compared with the expense that for this reason only it must at no distant time be nearly abandoned."

Revolts at home

The years 1830-32 also saw the Swing Rising in Britain, revolution in France, a major slave revolt in Jamaica and the parliamentary Reform Act. All led to the 1833 Slave Emancipation Act, which freed the 540,000 slaves in the British West Indies. Parliament gave the planters £20 million (£1 billion in today's money) as compensation for the loss of their slaves. The working class paid the money in tax, though they pointed out that the Church should have paid, as it owned so many slaves itself and as its priests justified the slavery of both black and white, at home and abroad. The Empire then imposed another form of servitude on the "freed" slaves of the West Indies – compulsory six-year "apprenticeships". Later in the century, it used indentured labour, with workers forcibly imported from India.

Slavery had been profitable in the 18th century; abolition was even more profitable in the 19th. The effort to "stop the foreign slave trade" was designed to damage rival empires and to protect the West Indies planters, now denied annual slave imports, from competition by sugar producers Cuba and Brazil, still reliant on buying slaves. The suppression of the slave trade on Africa's West and East coasts brought ever-closer control of West and East Africa, at first by private com-panies like the British East Africa Company, later by the Empire itself. Abolition was a weapon to expand the empire.

Throughout the century, the Empire continued to steal people, land and resources from Africa, reinforcing slavery there and killing millions of African people. The Empire continued to contribute to and profit from the slave trade well into the twentieth century. As Marx wrote, slavery is "what the bourgeoisie makes of itself and of the labourer, wherever it can without restraint model the world after its own image."

Abolitionism was an early form of the fake internationalism we see today – LiveAid, Live Earth, Blairite calls to intervene everywhere, Oxfam's delusions about Britain being "a force for good on the world stage". We would be satisfied if Britain was a force for good in Britain, and the world better served.

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Aug 17, 2013 9:12:49 GMT

Apologise? What for?

WORKERS, MAY 2007 ISSUE

There's a lot of sanctimonious drivel talked about the slave trade and its so-called abolition (see Abolition? What abolition?, p11). And none more sanctimonious nor drivelling than London Mayor Livingstone, "apologising" for London's alleged role.

But it wasn't London, it was the ruling class. And they started with London street children, then rebels, then the Irish, and when they had run out of them looked to Africa. Now open borders are allowing modern-day slavery in domestic service and prostitution in London.

London's workers have nothing to apologise for. Livingstone should apologise to them.

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Likely as not, there will be a long wait,for an apology to London Workers. Livingstone still has not issued an apology for crossing our Tube Workers Picket Lines. Ha HA!--the Great 'lefty' hope. Small wonder he was not re-elected. His friends in Brussels looked on askance. We secured our conditions of service and privatization was left a shambles. Pension protected. Worthless his resorting to platitudes about skin pigments, that was met with derision. Not least in Transport Canteens. More Tragi--than comiical--though still hilarious. Livingstone,"Red Ken," as always, "put not thy faith in false prophets." I wore out shoe leather getting him elected, first time he was elected Mayor. Shame on him. Did not repeat my folly. So not so much shame on me. Though it still renkles.

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Aug 26, 2013 15:40:37 GMT

www.workers.org.uk/features/feat_0106/reformation.html

At a time when the government is trying to make religious bigotry a duty, it's good to remember how Britain dispensed 500 years ago with shrines, relics, pilgrimages superstition and religious decrees – and with religious rule...

In praise of the Reformation

WORKERS, JAN 2006 ISSUE

The Reformation in Britain was largely created by the ordinary people of Britain, those who had developed a strong dislike for the Church's pomp, ceremony, fasting and holy days, its cults of saints and veneration of images and relics, and its beliefs in ghosts, angels and demons. Having less emotional and financial investment in the old order than did the clergy and the landed class, they saw through the mysteries, signs and wonders of the Church, and its obsessions with Dooms and Last Days.

They opposed shrines and pilgrimages, indulgences (remissions of punishment for sins), pardons, the Latin Mass and the cult of intercession on behalf of the dead in Purgatory. They rejected the monastic ideal, which neglected the service of widows, children and the poor in the selfish quest of personal salvation.

They opposed the hierarchical, compulsorily celibate, mediating priesthood, and a church hierarchy that claimed proprietorial rights over what people should think and believe.

They opposed church decrees (canon law) and the power of the Pope. They forbade appeals to the Pope and payments such as annates and Peter's pence. They opposed the claims of revealed religion and the all-embracing medieval Western church, which sought to override the sovereignty and independence of Britain.

They moved against the religious corporations, the Pope's fortresses, which ran vast estates and made huge profits. In 1535 the monasteries' total net income was £140,000, when the Crown's was £100,000.

Indulgences

The sale of indulgences, from a print by Holbein.

The monasteries were rentiers for two-thirds of their income, from whole estates put out to farm, from rents taken from smallholders, from tenements and from woods. Even their historian, Dom David Knowles, admitted, "monks and canons of England had been living on a scale of personal comfort and corporate magnificence which were neither necessary for, nor consistent with, the fashion of life indicated by their rule and early institutions."

By the Act of Supremacy of 1534, the monarch became the head of the Church of England, able to appoint its leading officials and determine its doctrine. The Church would no longer be a part of an international organisation, but a part of the British state, tamed and subordinate. Henry VIII permanently suspended the study of canon law in the universities.

A series of laws between 1532 and 1540 destroyed monastic life in England and Wales and in half of Ireland too. In 1535 Henry ordered visits to the smaller monastic houses to ensure that they shall "show no reliques, or feyned miracles, for increase of lucre". The Act of Suppression of 1536 ended 376 of the smaller houses. In 1538 Henry dissolved the friaries, which were centralised on the papacy. He dissolved the gilds, voluntary organisations where clergy prayed for the gild's membership.

The Injunctions of 1538 opposed "wandering to pilgrimages, offering of money, candles or tapers to images or relics, or kissing or licking the same, saying over a number of beads, not understood or minded on". In 1539 Henry suppressed the rest of the houses. The Injunction of 1547, Edward VI's first year, was to destroy all shrines, covering of shrines, all tables, candlesticks, trindles or rolls of wax, pictures, paintings and all other monuments of feigned miracles, pilgrimages, idolatry and superstition.

The state finally dissolved the chantries – chapels where priests sang masses for the founder's soul – and abolished the laws against heresy.

In the parishes of England, all that sustained the old devotion was attacked. The church furniture and images came down, the Mass was abolished, Mass-books and breviaries surrendered. The altars, veils and vestments, chalices and chests and hangings all were gone, the niches were empty and the walls were whitened.

Land and properties were seized and sold to landowners and capitalist farmers, making the settlement impossible to reverse. Queen Mary tried to re-establish Catholicism, but without the support of the religious orders, Mary's effort was doomed. Her failure proved that there was no going back. Monasticism, a major factor in the medieval world ever since the fall of the Roman Empire, was over.

Bible in English

The Reformation made the Bible available in English, stimulating reading and the English language and ending the priestly monopoly of learning. It urged people to go back to the sources. It stimulated people to think for themselves, actively to compare and assess, rather than passively contemplate and acquiesce. Doubts were welded into a systematic and self-confident confrontation with all religious tradition, against all orthodoxy.

The Reformation enabled the development of science and of industry, of history and archaeology, promoting the rational investigation of empirical evidence instead of relying on texts and authorities, and ignoring the pressures from church and state. Amid the complexities and divisions of the Protestant world, there was more room to manoeuvre, to question and innovate.

Finally, the Reformation asserted the sovereignty and independence of Britain, a nation free from foreign ownership and control, "a noble and puissant nation rousing herself like a strong man after sleep, and shaking her invincible locks", in Milton's magnificent words.

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Aug 30, 2013 7:05:16 GMT

Fine account of a murderous business, 30 April 2008

This William Podmore review is from: The Slave Ship: A Human History (Hardcover)

Marcus Rediker, of Pittsburgh University's History Department, has written a brilliant account of the machine that enabled history's largest forced migration. Exploration, settlement, production and trade all required massive fleets of ships. The slave ships, with names like Liberty, Free Love and Delight, transported both the expropriated labourers and the new commodities that they produced. The ships were weapons, factories and prisons too.

These ships were the key to an entire phase of capitalist expansion. Between the late 15th century and the late 19th century, it is estimated that they transported 10.6 million people, of whom 1.5 million died in the first year of slavery. 1.8 million had died en route to Africa's coast, and 1.8 million died on the ships. So the trade killed more than five million people.

The 18th century was the worst century, in which seven million people were transported, three million of them in British and US ships, from Liverpool, Bristol and London. Seven million slaves were bought in Britain's sugar islands, for toil in the plantations.

For half the 18th century, Britain was at war with France or Spain, for markets and empire. The slaver merchant capitalists gained from it all. They hired the captains and the captains hired the sailors. The conflict between these two forces was the primary contradiction on board, until the ships reached the African coast, then all united against the slaves. The captains exercised the discipline of exemplary violence against slaves and sailors. Their cruelty and terror were not individual quirks but were built in to `the general cruelty of the system'.

Rediker studies the conflicts, cooperation and culture of the enslaved. He shows how the enslaved Africans were the primary, and first, abolitionists, supported by dissident sailors and antislavery activists like Thomas Clarkson.

The book renders the sheer horror of the experiences that this vile trade inflicted on people. Rediker concludes, "we must remember that such horrors have always been, and remain, central to the making of global capitalism." The British Empire, so romanticised by Brown, Blair and a horde of self-publicising sycophants, was built on this murderous trade.

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Sept 1, 2013 6:34:07 GMT

Deemed not respectable enough by the labour movement’s later historians – they dismissed ..“Luddites” from their accounts.

The early 1800s: national workers’ organisation arrives

WORKERS, SEP 2013 ISSUE

It was during the first half of the 1800s that a nationally organised working class first emerged throughout Britain with centres in for example Sheffield, Birmingham, Leeds, Nottingham, Glasgow and the West Country.

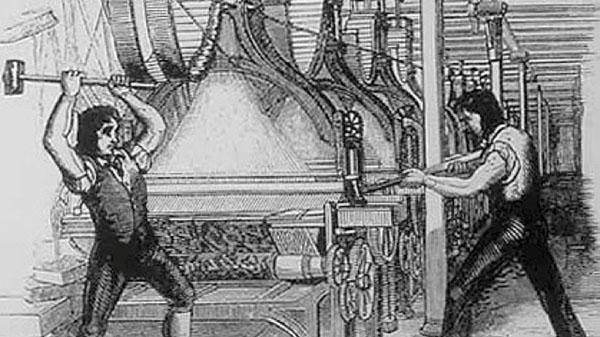

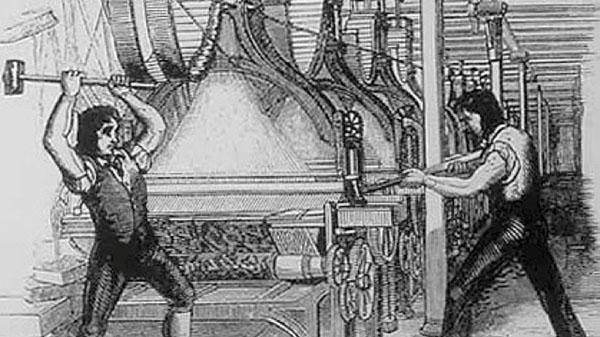

luddites

Contemporary portrayal of machine-breaking

The early vanguard were the clothing workers, known as “croppers”, who had become strong enough to enforce a closed shop in many of the workshops in Wiltshire and Yorkshire. Parliament by 1806 had been warned that a croppers system “exists more in general consent to the few simple rules of their union”. Until then croppers had evaded all chance of conviction for “combination”. They had formed themselves into a “club” and had accumulated over £1000 to provide for their members in the event of sickness preventing them from being able to work.

The croppers were also in correspondence with the cotton weavers, who through combination had formed an impressive nationwide union that existed from 1809 to 1812. With its centre in Glasgow it had strongholds nationally including Manchester and throughout Lancashire, Cumbria, Scotland, and Carlisle.

Strike

By 1811 the weavers could raise 40,000 signatures in Manchester, 30,000 in Scotland and 7,000 in Bolton. A disciplined and well supported weavers’ strike from Aberdeen to Carlisle then took place in 1812 with the aim of securing a minimum wage. The strike was eventually broken when the Glasgow leaders were arrested and jailed, with sentences ranging from four to eighteen months. The ruling class feared Britain was on a direct road to an open insurrection, so unions had to be broken.

Responding to what had happened to the Glasgow weavers, Luddism, which had been first deployed in Wiltshire in 1802, then took up the baton. It moved out from the grievance of the croppers to more general revolutionary aims among weavers, colliers and cotton spinners. “It is a movement of the people’s own” was how William Cobbett, a political commentator of the day, described it.

The Luddites are normally portrayed as a lunatic irresponsible fringe that stood in the way of progress by trying to wreck factory machinery. But Luddite opposition to machinery was far from unthinking. Along with machine breaking they made proposals for the gradual introduction of mechanisation, with alternative employment to be found for displaced workers, or by a tax of 6d. per yard upon cloth dressed by machinery, to be used as a fund for the unemployed seeking work. All of the proposals were rejected by the employers.

The focus in portraying Luddites simply as machine breakers was initially founded by Fabian historians (the Hammonds and the Webbs) writing in the late 1890s and early 1900s. The Fabians took it upon themselves to pioneer the written historical study of the early labour movement. Their aim was to portray the period 1800 to 1850 in the narrow context of the subsequent Parliamentary Reform Acts used to widen the vote from the 1860s onwards and to link this to the growth of the Labour Party during the early 1900s. They did not see Luddites as satisfactory forerunners of the “Labour movement”. So Luddites merited neither sympathy nor close attention.

Liberal and conservative historians decided among themselves during the early 1900s that “history” would deal fairly with the Tolpuddle Martyrs but the men executed for Luddism between 1812 to 1819 should be forgotten – or, if remembered, thought of as simpletons or people tainted with criminal folly. The Fabian view persists to this day in many quarters. But the facts tell a different story.

Politics

Rather than simpletons “Luddites and Politics were closely connected” shouted Thomas Savage in 1817 just before he and five other Luddites were executed at Leicester. In November 1816, 14 Luddites went to the scaffold in York defiantly singing “Behold the Saviour of Mankind”. Asked whether the 14 should all be hung simultaneously on a single beam the presiding judge replied, “Well no, sir, I consider they would hang more comfortably on two.” Their relatives were not allowed to bury the bodies.

A similar thing happened in Nottingham when 3,000 mourners went to the funeral after the hanging of Jem Towle, a leading Luddite – but magistrates prevented the funeral service being read. A friend later said, “It did not signify to Jem, for he wanted no Parsons about him.”

The Luddites, from 1812 to 1819, were the first to launch the agitations which led to the 10-hour movement during the 1840s. It was they who said that if a new machine were to be introduced the extra value generated should mean workers do fewer hours for the same or more pay or be redeployed. In particular they argued that child labour should be curtailed in factories as part of negotiating the introduction of new machinery. In “polite circles” at the time, factory child labour was considered “busy, industrious and useful”.

The employing class, its government and its snivelling apologists hated the Luddites so much because of their thought-through views on political economy. It was these ideas, not the cowardly gradualism encouraged by the Fabians, that eventually led to self-confident British trade unionism. In keeping with the recent victory over Napoleon and his designs on Europe, the call by workers in 1816 was ‘‘Ludds do your duty well. It’s a Waterloo job, by God.’’

The Luddites were renowned for their organisational skills, and through their transition towards collective bargaining after 1819 applied those skills to developing the British trade union movement. Many of them for the rest of their lives were involved with the social movements that followed. It was Marx and Engels who keenly identified in the passing of the 10-hour bill in 1847 that “for the first time•in broad daylight” the political economy of the working class was in the ascendency.

In 1834 the Whig Ministry, shortly after widening the vote to include the new factory owners, sanctioned the transportation of the labourers from Tolpuddle for the insolence of trade unionism, which by now was already firmly rooted elsewhere. The sour fruits of Parliamentary Reform had been anticipated by comments in the Poor Man’s Guardian by a worker from Macclesfield on 10 December 1831. He reckoned that “it mattered not to him whether he was governed by a boroughmonger, or a whoremonger, or a cheesemonger, if the system of monopoly and corruption was still to be upheld’’. What is most revealing from this period is the way British working people in the teeth of a ruthless enemy created a political force without negative and petty regional division between the North and South of our country. ■

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Oct 21, 2013 11:21:09 GMT

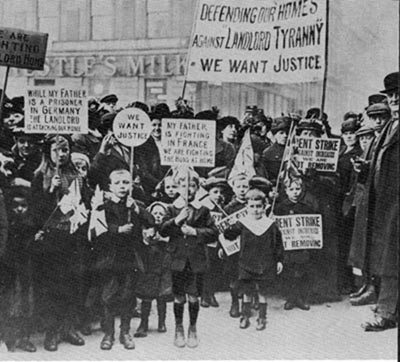

It began with the reasonable demand for a 40-hour week, led to a demonstration by 35,000 workers at Glasgow’s City Chambers – and howitzers around the city centre…

The day the Army was sent to the streets of Glasgow

WORKERS, MARCH 2010 ISSUE NINETY YEARS ago in the aftermath of years of capitalist crisis and the “War to end all Wars”, the British government had the military on alert to deal with a working class response it feared. Organised workers had forged strong links between centres of heavy industry, particularly in Sheffield, Newcastle and Glasgow.

The ties were strongest among those working in engineering and shipbuilding. Even in the midst of the First World War, those workers had resisted the imposition of the Munitions Act, the Dilution of Labour Act and Defence of the Realm Act, all giving government draconian powers to negate long-fought-for pay rates and conditions for skilled work, and to crack down on opposition.

Social unrest grew too, with well organised campaigns such as the Glasgow Rent Strike of 1916. One of the leaders was suffragette and communist Helen Crawfurd, who helped forge close links between the Clyde Workers Committee (CWC) and the Glasgow Women’s Housing Association.

Organisation

Organisation was key, too, in the growth of the CWC itself, bringing together shop stewards, delegates and the Trades Union Councils. Its strength was demonstrated by the chasing off stage of the Prime Minister of the day, Lloyd George, at a showcase rally at Christmas, 1915, intended to promote the need for his various draconian Acts. The 3000 shop stewards and union delegates then took over the meeting.

The only newspaper to report this, FORWARD (with a circulation of over 30,000), was suppressed by the military. The smaller VANGUARD , inspired by Bolshevism, was also closed. Copies of FORWARD were even confiscated from newsagents and regular readers’ homes. However, only a week later, the CWC launched its own journal THE WORKER – ORGAN OF WORKERS’ COMMITTEES OF SCOTLAND. It ran to five issues before the editorial team and printer were arrested and most jailed for a year. It had featured the defiant statement:

“The British authorities having adopted the methods of Russian despotism, British workers may have to understudy Russian revolutionary methods of evasion… but here is THE WORKER once again, symbolical of the fact that the cause of Labour can never be suppressed. It may be and has been bamboozled, hoodwinked, side-tracked and misled; it may be browbeaten, persecuted and driven underground, but it cannot be killed; and just when its enemies think they have finally subdued and made an end of it, it emerges more virile and vigorous than ever.”

Workers organising was nothing new — the weavers of Glasgow’s Calton district were strong enough to engage in a long and bitter dispute over wages and basic justice in 1787, only ending when several were killed by government forces. An insurrection in 1820 had ended in death and deportation, and Glasgow Trades Union Council was one of the earliest in Britain over 150 years ago.

By 1918, the combination of people’s high expectations of peacetime and demands of the returning troops and sailors gave the government a dread of the influence of the world-changing actions carried out by workers in other lands.

Particularly on their minds were the 1916 uprising in Ireland, the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 in Russia and the build up to what was an almost successful revolution in Germany in 1919.

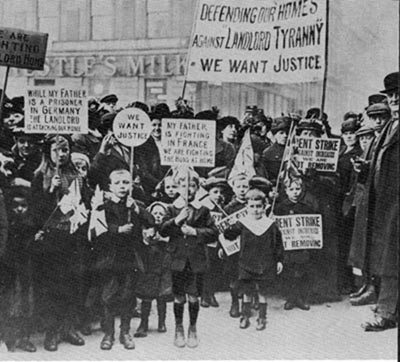

Right: Glasgow rent strike, 1916. Left: three years on, and tanks are stationed in Glasgow on Churchill’s orders as mass action grew.

Hence the reasonable demand for a 40-hour working week led to what became known as Black Friday, 5 February 1919. That day months of CWC agitation culminated in a mass demonstration of over 35,000 workers at the City Chambers in George Square in Glasgow city centre. It was attacked viciously by police and serious rioting ensued.

Tanks and troops

Its Britain-wide implications were made clear by the actions of Churchill and his Cabinet in ordering tanks and troops into the city. Local soldiers were confined to barracks, while the troops brought in were from well outwith the area. Machinegun nests on rooftops and even howitzers were positioned around the city centre.

However, although well organised and with a popular following, the workers committees were from a defensive tradition, of a trade union nature. They were coping with appalling conditions and the fear of looming mass unemployment. And there was nothing in the form of a Bolshevik or communist party in Britain at that time to inspire the struggle to go to a more ambitious stage.

It was perhaps no accident that diversions into nationalism and separatism – aimed at smashing the necessary British class unity – were concocted at this time. 1920 saw the formation of the Scots National League, John MacLean entering the cul-de-sac of Scottish republicanism and poet Hugh MacDiarmid writing his PLEA FOR A SCOTTISH FASCISM calling for socialism to develop “a fascist rather than a Bolshevik spirit”.

Others, including speakers at the 1915 and 1919 rallies, walked off into benign parliamentary social democracy. Kirkwood became Baron Bearsden; Mitchell hardly spoke in parliament; Maxton faded with the Independent Labour Party and Gallagher was an isolated communist voice at Westminster.

Helen Crawfurd went on to play a leading role in the Workers International Relief Organisation, set up to defend the Russian Revolution, having met Lenin in 1920. She was politically active until her death in 1954, being elected as a communist to the town council in Dunoon, Argyllshire, in 1946.

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Nov 17, 2013 14:27:29 GMT

Despite having no representation in parliament, the British working class were able to restrain the pro-slavery leanings of the ruling class...

1861–1865: British workers and the American civil war

WORKERS, JUNE 2012 ISSUE

In December 1860, 11 slave-owning states broke away from the United States of America to form the Confederacy. When Abraham Lincoln became President in March 1861, he denounced the secession as unconstitutional. April saw a Union blockade of Confederate ports and the onset of a bitter civil war.

Between 1840 and 1860 the United States provided 80 per cent of Britain’s cotton. The Confederacy thought “cotton famine” caused by the blockade would cut off Lancashire’s textile industry from its supplies of raw materials and propel Britain into conflict against the Union to end the blockade. But matters did not develop in that way.

Great distress overwhelmed the British cotton industry. Between 1861 and 1865 the Lancashire textile industry suffered a period of severe unemployment with over 320,000 workers unemployed out of 533,950 by November 1862; there were still 190,000 fewer jobs in December 1864.

Fairly ample stocks of cotton had been stored in British factories and warehouses. It was the speculative bidding up of the price for raw cotton that did damage, particularly hitting smaller manufacturers who could not withstand the strains of the high price. The crisis in the textile industry also gave British manufacturers the opportunity to extend the working day, depress wages and equip factories with labour-saving machinery.

The civil war acutely divided British opinion. Friends of the Confederacy in Britain came largely from the aristocracy (who had social and political ties with American slave-owners) and the commercial classes (who had business links and wanted to escape Union tariffs). These upper classes dominated parliament. Their newspapers – such as The Times – openly advocated aiding the Confederacy.

British workers transcended narrow economic self-interest to support the Union cause.

But British workers, driven by a deep hatred of slavery and striving for a more democratic government at home, restrained the pro-confederate leanings of the government class. Though not represented in parliament, the working class was the preponderant part of society and therefore not without political influence, able to pressure the government into adopting a policy of non-intervention in the civil war and thwarting assistance to the Confederate States.

At the beginning, northern US leaders asserted the main object of war was to preserve the Union and not to touch slavery. Lincoln’s Emancipation of the Slaves Proclamation strengthened British workers’ support for the Union cause. The spinners and weavers of Lancashire transcended their economic self-interest and took the lead in upholding the Union blockade. They realised that helping the slave-owners win would defeat the cause of freedom represented by the North and set back their own struggle for political reform in Britain.

Massive meetings

Throughout 1862 and 1863, massive pro-Union meetings were held by workers in Ashton-under-Lyne, Blackburn, Bury, Stalybridge, Liverpool, Rochdale, Leeds, London and Edinburgh, calling on the government to not depart from strict neutrality in the conflict. On 31 December 1862, thousands of working men in the Manchester Free Trade Hall expressed sympathy with the North and called for Lincoln to eradicate slavery.

The efforts of those seeking to glorify the slave power and corrupt the minds of working people were utterly in vain. Working-class newspapers not only printed the Manchester meeting’s Address to Lincoln but also President Lincoln’s reply recognising British workers’ sacrifice.

In order to ascertain the effects of the “cotton famine”, The New York Times sent a reporter to Lancashire in September 1862 who reported on the acute distress of the cotton manufacturing workers and came up with a practical suggestion – launching a campaign to send food aid supplies to Lancashire workers.

Meetings were held and money raised throughout the Union. On 9 January 1863, the George Griswold relief ship, loaded with gifts of food, left New York to the cheers of spectators. Her cargo consisted of flour, bacon, pork, corn, bread, wheat and rice. American stevedores loaded the ship without charge. Additional ships were soon sent: the Achilles and the Hope.

When the Griswold docked at Liverpool, all the dock workers refused payment for their services and the railways offered free transport. On 23 February 1863, 6,000 working men were at the Free Trade Hall (inside and out) to greet the arrival of the George Griswold. One speaker observed, “If the North succeeded, liberty would be stimulated and encouraged in every country on the face of the earth; if they failed, despotism, like a great pall, would envelop our social and political institutions.”

‘The cause of labour is one’

On 26 March 1863, 3,000 skilled workers at St James Hall assembled in a pro-Union gathering organised by the London Trades Council to hear trade union speakers including a bricklayer, engineer, shoemaker, compositor, mason and joiner. Two contributors noted: “The cause of labour is one, all over the world” and “We are met here ... not merely as friends of Emancipation, but as friends of Reform.” With the North’s victory, a working class newspaper wrote “No nation is really strong where the majority of its citizens are deprived of a voice in the management of public affairs.”

As a result of working-class resistance, Britain neither recognised the Confederacy nor intervened to break the blockade. Despite terrible hardships, particularly in the northwest, workers refused to allow their sufferings to be exploited by pro-Confederate sympathisers.

As Marx said, “It was not the wisdom of the ruling classes but the heroic resistance to their criminal folly by the working classes of England that saved the West of Europe from plunging headlong into an infamous crusade for the perpetuation of slavery on the other side of the Atlantic.”

The American Civil War generated a broadening of horizons among British workers that blossomed even further in the First International.

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Nov 26, 2013 10:07:03 GMT

www.workers.org.uk/features/feat_0910/combination.htmlCapitalists and workers are engaged in a constant battle to exert influence and control over pay and conditions as the two classes contend in the sphere of work and industry. This is as true now as it was at the birth of our class several centuries ago…

Unions in illegality: the Combination Acts of 1799 and 1800

WORKERS, SEPT 2010 ISSUE When the 18th century began, the guild system still applied. A guild comprised several kinds of "class": from the merchants (or large masters) to the apprentices, though power rested in the hands of the merchants. Therefore small masters and journeymen began to form unions of their own to protect themselves and their interests. Nevertheless they failed to obtain incorporation or the right to create combinations, effectively compelled to secrecy when it came to organisation.

During the 18th century, mercantilist capitalism gradually gave way to industrial capital. The old methods of wage fixing became ineffective. A rising class of capitalist employers prompted the emergence of defensive labour organisations, combinations of workmen whose cooperation was the only means at their disposal for survival and protection. The combinations, embryo trade unions, were mostly of skilled and semi-skilled workers, artisans and craftsmen. They aimed to achieve abolition of the worst evils of the capitalist system and some improvement of living conditions. More and more trade clubs or societies were seeking to fix wages and conditions by collective bargaining. Employers resisted these efforts, constantly petitioning the government to uphold ‘ancient law’ and suppress the ‘unlawful’ organisations of workers.

Class clashes were numerous: 383 disputes were recorded between 1717 and 1800, but most incidents went unrecorded or were settled without recourse to law or officialdom. Most of the disputes centred on wages. In 1766 the shipwrights of Exeter, for example, decided not to work for masters who were seeking to employ them at "less wages than have been from time immemorially paid to journeymen shipwrights" and imposing longer hours than had been "usual and customary".

Some combinations were powerful and effective, threatening their masters to "strike and turn out” if their demands were not satisfied. During the 18th century, many acts were passed outlawing combination in one specific trade or another, as for example in 1718 against wool combers and weavers. In the same period workers lost several laws affording limited protection in this or that industry.

Repressive

Although the launch of the proceedings remained in the hands of the employers, the Combination Acts brought the government into a more repressive role against trade unionism because of fears that it would spread to the newly industrialised regions, especially the Midlands and the North, a goal only partially achieved.

The Battle of Waterloo: it marked the end of the Napoleonic Wars,

but not of the anti-union legislation brought in during them.

The outbreak of war against revolutionary France intensified these fears because it was thought that revolutionary ideas would spread among the working class and that the unions would become centres of political agitation.

So at the end of the century, the government gave the “masters” complete control of their workers. As the Industrial Revolution in Britain got underway, all the legal restraints on workers in particular industries were standardised into a general law for the whole of industry. All the regulations and laws that recognised a worker as a person with rights were withdrawn or became inoperative. Initially, the act against illegal oaths was used to break up the existing trade unions. Then, the Combination Acts of 1799 and 1800, originally specific to the millwrights, were turned into a general prohibition and outlawing of trade unionism.

The acts forbade any combinations of workers to act together to improve their wages, reduce working hours or otherwise change their conditions of labour, with any violation punishable by three months imprisonment, or two months of hard labour. Magistrates, who were usually agreeable to the employers, passed sentence. It was the first time that penalties were prescribed for workmen as a class.

Ingenuity

With trade union organisations declared illegal, workers hoodwinked their opponents by reappearing as mutual benefit associations or similar bodies. (There are no limits to human ingenuity.) A large number of secret organisations carried on the fight against the employers and spurred the workers into resistance.

Where the government partially managed to constrain trade union development and activity, it did so more as intimidation than through undertaking prosecutions. Unions operated in a context of risk rather than of full and constant constraint. Over twenty-five years of illegality, the Combination Acts did not stop workers’ organisation nor were they totally enforced.

Convicted

Thousands of journeymen were convicted under these Acts, whereas no one employer was. The Times Compositors Union was suppressed in 1810 after they asked for a rise in their wages. Workers employed in the new factories and mines were constantly persecuted and often forced to combine secretly, for instance the iron founders in southern Wales. Resentment grew into opposition, most notably in the Luddite rebellions of 1811 and 1813 (to be featured in a forthcoming ‘Historic Notes’).

Introduced in wartime, the acts were not repealed with the return of peace in 1815. Repeal came in 1824, celebrated by an outburst of strikes. In 1825 a less stringent law was put in their place.

The temper of young industrial capitalism was harsh. Workers were refused education, political rights and any voice in their conditions of employment but they did not succumb and found ways to make progress.

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Dec 30, 2013 7:24:28 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Jan 11, 2014 6:40:33 GMT

As the National Health Service reaches its 60th anniversary, it's time to look back and explode some myths about who created it, and why... The NHS at 60: not given to us by Labour, but fought for and won by workersWORKERS, JULY 2008 ISSUE The National Health Service came into being on 5 July 1948, and has played a major part in the quality of our lives ever since. Most people in the UK have known no other way of providing medical care. The NHS faces many threats and challenges despite all its successes. The alleged need to improve patient choice is pushing many changes, not all of them welcomed by patients and health workers.

Medical care has advanced beyond belief compared to 1948. The NHS today employs 1.3 million workers, with an annual budget of over £100 billion. It is organised into many different trusts, which compete for patients and funds. Some will soon have "foundation" status with even greater independence. Financial performance is as important as clinical in deciding which trusts have resources.

The government promotes the Private Finance Initiative (PFI) and private/public partnerships (PPP) in the belief that "the market" is the best way to exercise financial control. But it does not talk about the huge future costs these entail, or the effect on clinical decisions.

When the NHS was created, patients were promised "your own doctor". Superficially the promise of greater choice is a progression from that promise. But it's worth looking in more detail at the reasons for creating the NHS. Two days before the NHS came into being Health Minister Aneurin Bevan wrote the following in the British Medical Journal:

"On July 5 there is no reason why the whole of the doctor-patient relationship should not be freed from what most of us feel should be irrelevant to it, the money factor, the collection of fees or thinking how to pay fees – an aspect of practice already distasteful to many practitioners.

"The cost of ill-health is a burden on the community and a burden on the family, and the startling advances made by Medicine in the past 25 years have steeply increased this cost. There is, therefore, a logical case for spreading it over the whole of the community so that those who are fortunate enough to remain in good health may help those who temporarily fall out of the ranks.

"The price Britain will have to pay for this new service is high, but the fact that the country is prepared to pay this high price shows that it is well aware that on the crude economic level an efficient and complete medical service will pay a good dividend in health, happiness, and efficiency in work".

The NHS was not a creation of the Labour Party, given out of generosity. Lord Beveridge, whose report recommended setting up a national health service, was anyway a prominent Liberal. The NHS was fought for and won by pressure from workers. Health provision was one of the reasons a Labour government was put into power in 1945 (and again in 1997).

The impetus for providing standardised comprehensive health care services came in the wake of the industrial revolution. Britain was transformed with great rapidity from an agrarian, rural nation into an industrial, urban one in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. People congregated in towns and cities, which produced an explosion of disease, industrial injuries and destitution. Lack of clean water, drainage and refuse disposal were major contributory causes of disease, particularly of cholera outbreaks.

Royal Commission

A Royal Commission was convened in 1832 under the stewardship of Edwin Chadwick, to examine the problems of urban poverty. This gave rise to the establishment of a Public Health Board, with him as Chairman, following the passage of the Poor Law Amendment Act in 1834. He subsequently produced a paper entitled "Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain", which was the chief stimulus behind the Victorian Public Health Movement. The first Public Health Act went onto the statute books in 1848; from then it became generally accepted that the health of the population was the responsibility of society as a whole.

November 2007: Marching in London for the National Health Service

in a demonstration called by Unison.

Photo: Workers

Health services in Britain emanated directly from industrialisation and the needs of the manufacturing base. It is not a question of chicken and egg. Wealth creation and health are linked inextricably.

The National Insurance Act of 1911, passed under Lloyd George, represented the most important direct intervention by the state into health care prior to 1948. It introduced a compulsory system of contributory health insurance for a major section of the manual workforce. It was known as the "10 pence for 4 pence scheme". At the outset 11.5 million workers were covered, rising to 20.3 million by 1938, which was 43 per cent of the population. The income limit for participation was extended from £160 a year to £250 in 1920. In addition to a weekly receipt of sickness benefit, members and their families were eligible for adequate medical attendance and treatment, without further payment, from their chosen "panel" doctor. By 1938, 90 per cent of all active general practitioners were involved in the scheme. Hospital treatment was excluded, except for tuberculosis.

After the 1914-18 war, Lloyd George, under pressure to create a "home fit for heroes", commissioned the Dawson Report. This proposed the need for a nationally organised comprehensive health system with primary and secondary health services, specialist services for infectious diseases and mental illness, and teaching hospitals with medical schools.

The first Ministry of Health was established in 1919 with a doctor, Christopher Addison, at its head. During the interwar economic depression, Neville Chamberlain was minister from 1924-1929, and briefly also in 1929 and 1931. He was forced by the electorate to support a whole series of laws comprising 25 Acts of Parliament which brought all Health and Poor Law services into a single scheme, and extended access to health insurance and pensions. The 1929 Local Government Act is of particular significance.

At the outbreak of war in 1939, there were 3,000 hospitals in England and Wales of which 1,000 were voluntarily supported, with excellent standards and high calibre medical staff.

Of those, 300 hospitals specialised in a particular branch of medicine such as paediatrics, orthopaedics or ophthalmics. The remaining 700 were small cottage hospitals staffed by general practitioners.

In addition 2,000 local authority hospitals comprising the Poor Law Infirmaries provided a very basic standard of care for the elderly and chronically sick. There were 300 large hospitals for the mentally ill and about 50 infectious diseases hospitals established under 19th century sanitary legislation.

Between 1939 and 1946 events moved rapidly towards a proposal for a central government-directed and structured national health service. The Beveridge Report of 1942 promulgated the concept of comprehensive public protection for all individuals from "the cradle to the grave" against sickness, unemployment and poverty. Ernest Brown was Minister in 1942. The state, he said, will provide free medical care and pensions, family allowance, insurance against unemployment, improved housing and basic public health services. One-sixth of the cost would be met from National Insurance Contributions, five-sixths from the Exchequer.

No longer tolerable

Though differences existed between him and the doctors, the profession as a whole were no longer prepared to tolerate a situation whereby people hesitated to seek medical advice for fear of the cost that might be entailed by the discovery of a serious illness. No major operation or prolonged medical investigation could be allowed to impose a financial strain at a time when a family might be least able to bear it.

As we've seen, Bevan wanted to take money away from the relationship between patient and doctor. Labour wants to take the NHS in the opposite direction: monetary considerations are to the fore with direct and indirect privatisation of parts of the service and the increase of enterprises in health care with no purpose except to profit. But it's not only Labour – all parliamentary parties have similar views on "what we can afford".

The challenge for the working class in Britain is once again to assert the importance of the NHS to our health and to fight as much to maintain it as we did to create it and revive it. In the end it's us who will decide the future for NHS by taking action or failing to do so.

|

|