|

|

Post by dodger on Aug 31, 2013 20:44:11 GMT

"When we passed a column of Russian prisoners we saw how comparatively well-off we were. They were all skeleton-thin, with brave, sunken eyes burning out of skull-like faces covered in full, ragged beards. Their fanatical SS guards treated them like animals, herding them along with whips and rifle butts ... We could do very little, but one of us threw over some cigarettes. (Soon there) was a small, silent bombardment going on as the Russians smiled and clutched at this act as much for its humanity as for the much needed food. One pack of cigarettes fell short and a Russian prisoner eagerly reached out for it. One of their guards lifted his rifle and smashed it into the Russian's head as he stooped to pick up the cigarettes. When the man fell under the blow the SS man screamed at him and continued to smash him in the face and kick him like a dog. A collective roar of rage went up from our side of the road and several hundred Allied prisoners stopped and moved a few dangerous inches towards the Russian column ... The SS man giving the beating turned around and looked in total astonishment as it never occurred to him that anyone might object to his actions."

From Booklist From Booklist

Readers may be familiar with Stalag Luft III as the German prison camp that was the setting of the movie The Great Escape. Ash was a real-life prisoner there during World War II, and he spent most of his time there trying to escape. He was a "cooler king," a real-life version of the Steve McQueen character in the film: someone who alternated between planning escapes and whiling away the hours in solitary confinement after the various schemes failed. But, for Ash, unlike his fictional counterparts, life was not a lighthearted adventure. His entry into Occupied France was via an airplane crash, he was tortured by the Gestapo, he watched his friends and fellow prisoners gunned down while attempting their own breakouts. Like Paul Brickhill's Great Escape (the book on which the movie was loosely based) and other WWII lemme-outta-here stories, this memoir is full of excitement and drama. Fans of escape literature will eat it up. David Pitt

Review

"Totally spellbinding. Bill Ash makes Steve McQueen look like Jim Carrey"..."An astonishing tale - totally spellbinding. I always knew Bill Ash was a special guy but never realised how special... Perhaps his greatest achievement was to emerge from the horrors of the war with his faith in ordinary people enhanced" (

- Alan Plater

"A story of bravery, humor and never-say-die"

- The Times, London

"Under the Wire makes the reader want to stand up and cheer!"

- Charles Rollings, Wire & Walls

"One of the most inspirational stories I've ever read. A wonderful book about a wonderful man"

- Robert Elms, BBC

www.youtube.com/watch?v=wcXs80FE718

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Ash_(writer)

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Sept 1, 2013 7:55:15 GMT

WORKERS POLITICS the Ethics OF Socialism.

by William Ash

Published 2007

Bread Books, Coventry

As luck would have it, when Marx Library asked me to review William Ash’s new book Workers’ Politics the ethics of socialism I had only very recently put down Middle Sea: A History of the Mediterranean by John Julius Norwich and was enthusiastically burning the midnight oil working my way through My Life by Fidel Castro as told to his chosen biographer Ignacio Ramonet, editor of Le Monde Diplomatique.

Bill Ash’s book is about ethics and philosophy in general and it is divided into four easy to follow sections: Values, Obligations, Rights and Alienation and Political Change. Ethics he shows to be philosophy in practice. Values originate in the production of commodities and derive its conception and meaning in social relations of production. Obligations describe the bonds that exist between social beings in their quest to co-opt nature. Rights, evolve from notions of human equality and are a reflection of the “equalisation of human labour in general which is the source and measure of value”.

All practiced through the great panorama of class struggles for ascendancy and against the decomposition that make up the capitalist societies in which we live and struggle to fashion change.

All good and easy enough stuff to understand? If only life were so simple!

That is why I mention both a history of the Mediterranean and Fidel. All of the four categories Ash so eloquently unravels have their denouement in history or rather, in histories. In the history of the Mediterranean one can come to understand the development of the great civilisations, from Rome to Greece, taking in Byzantium and Venice en route, and the great religions Islam, Judaism and Christianity across hundreds of years, dynasties and social systems: nomadic and primitive communism, feudalism, mercantile capitalism, industrial capitalism and imperialism.

To get to grips with the concepts Bill describes, a thousand year history of the crucible of western societies is an excellent tableaux and testing ground.

My Life is important for two reasons in relation to Bill’s book. In the first, Castro is workers’ politics and ethics, in practice, in the most difficult of circumstances. A man who, across five decades, has been the object of so many assassination attempts by the USA and her supplicants in Miami is well placed to talk ethics and morality. He still sleeps in a different apartment most nights. My Life involves so many of the issues raised in Ash’s book particularly to do with morality, now so highly politicized. There is collective and individual rights and obligations, the right to life and the death penalty, the freedom to move in and out of a country, the right to exist as a country unhindered by external pressure and much more. In a recent interview in which he explained why he took the opportunity to interview Castro for so many hours over such a sustained period, Ramonet explained that, he thought My Life was important, “because the left has not done theory for thirty years.”

An important point and a genuine criticism of many, but I would humbly beg to differ. There have been people “doing theory” for the last thirty years and Bill Ash is among them. Indeed Workers’ Politics is a re working of a book that has seen a number of pressings since the early 1960s with publishers in the UK, USA and India - prestigious publishers such as Routledge and Monthly Review. Bread Books, a new publishing venture, should be commended for keeping this important work, updated, in print and in the public eye.

Ash – a one time President of the Writers’ Guild of Great Britain - has the advantage of being a writer by occupation [though in his hands it seems like he is a writer by birth] and is able to put across complex theories of social development, the development of knowledge and explain the origin of ‘thought’, in ways which open them up to a much broader audience. And philosophers who also want to change the world rather than obscure it or justify the politics of dismal capitalism are unfortunately in short supply.

The first three chapters remain topical and the last one more controversial. For these reasons alone the book is well worth the read. Most importantly, the book allows space for the reader to develop understanding as the proposition is revealed. You will not come out of this book without changing the thinking with which you picked it up.

Workers’ Politics shows how vulnerable capitalism is to a critique, which goes much broader than a denunciation of its economics of exploitation. Capitalism is revealed as shoddy. It shortchanges its participants, worker and capitalist alike. It hits us in pocket, but also in heart, mind and soul. Humanity is capable of so much more and so much better. All that is quality in our lives, from education at a local school to the struggle to defeat cancer, is a product of human struggle in the teeth of capitalism. How much better, Ash contends, would human endeavor be, if it were set to gel within a social system whose essence was satisfaction of collective interests. This will not be possible while surplus value, is appropriated by private hands.

Capitalism, Ash contends, is vulnerable if it is confronted as a system of values rather than piece-by-piece. He describes a broad front, which is a focus of real struggles of, ideas, culture, language, morality, ethics and philosophy at home and in the workplace. In his hands whole new aspects of Marxism as a critique of capitalism are engaged. Categories like ‘good’; ‘freedom’, ‘ought’, ‘solidarity’, ‘liberation’ and ‘value’ take on new strengths. It is territory any reader of the founders of English socialism such as Ernest Jones, George Harney, William Morris, Ruskin and Robert Owen or Walter Crane would be familiar and comfortable with.

Ash has grasped the importance of asserting the positives.

Instead of shoddy goods to be foisted on a public given no other option, we are encouraged to insist on new qualities. Human endeavor should be set free so that each can work with others to satisfy human needs. In place of the steady diet of war and aggression he posits international cooperation the better to grapple with global challenges. In place of mock freedoms parading as ‘rights’ as in the abuse of unionism and strike action to throttle Venezuela’s oil industry or truckers subverting elected governments in Chile, freedom of expression and association are enriched by freedom from exploitation. In Bill’s hand, ‘liberation’ is restored as a term of the people opposed to the sham ‘liberal’ democracy, enforced by a World Bank. Solidarity and the right to join a union are asserted over ‘freedom’ not to join. This is a world turned the right way up.

Ash leaves few stones unturned. He scrutinises language, ‘truth’, the meaning of ‘value’ which arises as a category in antiquity with the production of goods for human use, normative judgments, what is ‘good’ and the bonds that tie us such as friendship, family, class and fellowship. None of these he contends is absolute. All evolve historically and are determined by the relative strengths of the classes which contend for power in society. But his analysis puts to shame, the current fashion for unthinking labeling using throwaway concepts such as ‘fairness’, ‘sustainable’ and ‘equality’.

Ash shows that, at the root of all this dysfunction, lies alienation that arose with the division of labour. Bill returns time and again to Marx’s 1844 Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts and The German Ideology, two works deserving of much greater prominence and consideration. It was here Marx revealed that, in early commodity production, value and utility became separated as workers were separated and dispossessed of the tools that guaranteed their freedom as producers.

So much of modern day thought is anchored early on in the appearance of a division of labour and the appearance of labour power as a commodity. ‘Freedom’ is given to workers in the form of dispossession - i.e. they are free to starve or work. Ash observes, “The social fact of the division of labour implies a separation between productive effort and enjoyed satisfactions.” Much flows from this division. Our thoughts and definitions, our concepts and values are polarised. Ideas of ‘effort’ and ‘sacrifice’, of ‘quality’ and ‘fair’ remuneration are linked to production. Others, such as ‘emotion’, ‘image’ and ‘desire’ are linked to consumption. Production is collective and involves pooling of effort, interests and resource. Consumption is private and individualistic.

Try as it might, as a result of the division that sits as its inner core, capitalism cannot put these dynamics together. Instead it makes opposites of what should be unities: thinking and doing, town and country, reality and aspiration. As a result, it is unable to really satisfy human wants and desires. But it can and does sell them things, even when they do not want or need them. And what is foisted on them comes with built in obsolescence. With this goes a whole baggage of thinking and a value system, which Ash encourages us to challenge.

He points to the need to go beyond this capitalism to a society based on new sets of beliefs and values. In capitalism there is little joy of work which should be a noble pursuit, the pleasure in fashioning nature into value is pushed aside in the quest only for greater profit, the celebration of skill and collective endeavor at best begrudgingly rewarded. The motif of this new society would mean that, to quote Marx, “labour has become not only a means of life but itself is life’s prime want...”

Your reviewer found Chapter 3 the most interesting and topical. It analyses the scope and limits of freedom of choice. Socialism has taken a hiding in the last two decades in the name of freedom. The USSR never recovered from a crusade in the guise of ‘human rights’ launched under President Jimmy Carter in the mid 1970s and pursued under Reagan. Yet, in its early phase, socialism was the “watchword of liberty” and a hope of liberation for mankind.

The concept of freedom is loaded with the reality of class. Yet many on the left retreated from class during that period or gave prominence to aspects of class over the essence. It was precisely this retreat, which opened up the space for class rights to be supplanted in the popular mind with ‘human rights’, promoted zealously to this day by imperialism. It has been a hard struggle to regain the once firmly held high ground.

According to Bill, workers in eastern Europe were urged to assert a ‘right’ to withdraw their labour, yet when their counterparts sought to assert the same right under capitalism it was, “either at the wrong time, the wrong place or called for wrong reason.” In other words, class and the class struggle, lies at the root of rights and freedom.

The struggle over rights is pivotal to the direction of society today. Much of the passing confusion of the 1970s arose as a result of a misunderstanding of the relationship between individual and collective rights. Ash is spellbinding when he discusses this issue. The Marxist way, he reasons, is not to dismiss the rights or realities of individuals but sees individualism linked to consumption and as a destructive force. Instead, Marxists argue that the full flowering of individuals becomes possible when they recognise the collective nature of humanity and work to combine their unique character and talents, to harness nature for the good of all. That way each individual acts as a social agent.

Because of the peculiar historical strength of organised labour in Britain, it is mainly the study of the economics of Marx, which has prevailed. Yet Ash makes an excellent case for looking at the issue of philosophy, which dominated Marx’s life. According to Ash, the struggle to free ourselves from exploitation is “the struggle to uncover the true relationships between people and as producers, thereby allowing us to think in new ways as a result of being able to recognise reality for what it really is.” This is the process which Marx called “a class for itself”.

In the bibliography there is a treasure trove of books and reading for anyone interested in further exploration. Most are readily available to members of Marx Library. On visiting the library you may well find Bill, at 90 years old, now an elder statesman of the labour movement, working on his next project.

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Sept 1, 2013 8:03:47 GMT

Workers Politics, the Ethics of Socialism by William Ash; Bread Books, Coventry, UK; 2007; pp. 340.

www.mainstreamweekly.net/auteur115.html

Stimulating Exercise unfolding Socialist Future

K S Subramanium

This is a remarkable book by a remarkable author! William Ash is an acclaimed novelist, script editor, journalist and writer, decorated war hero, leading trade unionist and thinker! The publication of the book, a British reprint of an earlier book published in India in 1998 with a different title, coincided with the 90th birthday of the distinguished author. The book is a ‘clear, rooted account of the importance of socialist ideas within the Marxist tradition’. This timely exercise needed to be carried out especially at a time when there is considerable lack of clarity over how Marx actually reasoned philosophically and practically and how he came to his revolutionary conclusions, using as well as transcending the ideas of the greatest minds of his time with the result that, ever since Marx, ‘sociology has become in the works of Weber, Durkheim, Mead, Mannheim and so many others, a debate with Marx’. One must thank and compliment the author for writing this admirably solid book.

The author enters the Marxist terrain of ideas by examining ‘values’, ‘rights’, ‘obligations’ and ‘alienation and social change’. After a stimulating discussion of the first three topics, the author provides us in the final chapter an absorbing examination of some major developments in global politics. Alas, India does not figure in his treatment though there is a passing reference to the eminent Indian Marxist Randhir Singh, whose 1087 page monumental work, Crisis of Socialism (Ajanta, 2006) has provided a challenging view of the panorama of socialist issues in the world.

The author’s new preface to the book explains the context. Global political developments since 1998 have demonstrated the moral necessity of a socialist understanding of society as the basis for united action to end the exploitation of working people by capitalist corporatists and to contribute to the establishment of a free, peaceful and truly democratic world. The collapse of the Soviet Union was not the end of socialism; it was the end of state socialism which had been allowed to degenerate into bureaucratic stagnation. The end of the Cold War saw the establishment of global capitalism, in which huge corporations of the US play a prominent role. Speaking of Blair’s Britain (and Brown’s as well, one presumes), the author states: ‘Real socialists have to realise that just as Blair’s political rule has become indistinguishable from Thatcher’s, so social democracy under capitalism, will always turn into some kind of fascism.’ How about ‘social democracy’ in Manmohan Singh’s India?

The four chapters in the book clinically examine how ethics and morality relate to politics and economics. The first deals with ‘values’: what they mean and where they come from; the second, with the meaning of ‘normative judgments’: what makes things right or wrong; the third, with ‘obligations’, including a discussion of capitalist freedoms; and the fourth, ‘alienation’ and political change. The theoretical discussion in the first three chapters needs careful reading by the ordinary reader. The invigorating political analysis of global developments in the last is refreshing, rewarding and of outstanding quality.

¨

The author explains the limitations of bourgeois ethics and derives Marxist ethics from Marxist political economy and the theory of value. Scholars may feel that the author commits a ‘naturalistic fallacy’ and is logically unconvincing with a ‘logical blurring’ between what ‘is’ and what ‘ought’. However, the attempt is worth making and provides intellectual provocation. After dealing with the whole question of value by analysing the concept of ‘good’, the author tackles the issue of claims on people and things by analysing the concept of ‘right’. He then goes on to analyse the limits and scope of freedom of choice and action by looking at the concept of ‘ought’. The author’s discussion is based on the original texts of Karl Marx but he does not lightly bypass or carelessly dismiss the thought of other major non-Marxist philosophers and thinkers in the field. The discussion enables the reader to put the ideas of thinkers like Althusser, Bentham, Bradley, Carlyle, Durkheim, Hegel, Russell, Mannheim, Weber, Wittgenstein, Sartre et al., and concepts like ‘existentialism’, ‘post-modernism’ and ‘structuralism’ in perspective. The author’s encyclopaedic reading and clear understanding is compelling and evokes one’s admiration.

The final chapter contains an absorbing analysis of ‘alienation and political change’. Unlike, Hegel, Marx uncovered the roots of ‘alienation’ in social existence and traced its relations with other aspects of the material conditions of specific people in their actual productive relationships to a theory of social change which can be acted upon. ‘Private property’ is Marx’s expression for the objects produced by alienated labour which reaches its culmination in capitalist society. While discussing the role of the working class as an agent of social change, the author asks whether the British working class, particularly as organised in trade unions, is developing its own ideology, which can establish socialist society in the country. This leads him to a discussion of industrial action by the British working class in the recent period.

The discussion of ‘Marxist socialism in practice’, leads the author to an exploration of the experience of socialism in the Soviet Union culminating in its ultimate demise. He is of the view that the socio-economic system which collapsed in the Soviet Union in 1990-91 was certainly not a dictatorship of the proletariat, Marx’s name for democratic socialism in the period when there are still class enemies within the country and external enemies without. What collapsed was state socialism, which had been allowed to decline into bureaucratic stagnation. In a backward country such as Russia the dictatorship of the party on behalf of the working class was the only alternative to abandoning the post-revolutionary socialist vision of society altogether. After the death of Lenin, Stalin used the party-managed dictatorship of the proletariat to severely repress any criticism and did not advance working class political democracy. After Stalin’s death in 1953, Khrushchev used the same party dictatorship for an ill-thought-out and unrealistic policy of catching up with the West. The Gorbachev period witnessed the decline into state capitalism with all the accompanying features of ‘black marketing, currency swindles, protection rackets and the invasion of foreign entrepreneurs to cash in on the chaos’.

The author’s view is that the practice of socialism in the first workers’ state should be seen not as the end of socialism or of history but as the ‘first stage of a transition not unlike the passage through several centuries from feudalism to capitalism’. Randhir Singh is cited to the effect that ‘the transition from capitalism to socialism will also involve revolutions and counter-revolutions, victories and defeats, advances and retreats in the eventual transformation of capitalist barbarism into socialist civilisation’. Only, the transition will not take so long because it is a much more conscious development with the actors involved in the ideological conflict between capitalism and socialism ‘much clearer about the class interests, private profit or the collective good, which are respectively served’.

What stands out throughout the discussion is the author’s undying optimism of will against the pessimism of intellect while portraying some of the faltering steps taken by humanity in its march towards a truly ‘socialist’ future.

Bravo and thank you, Comrade William Ash, for providing us this exhilarating intellectual fare!The author is a Visiting Professor, Jamia Millia University, New Delhi. He can be contacted at e-mail: mani2002@gamil.com

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Jul 2, 2014 12:38:52 GMT

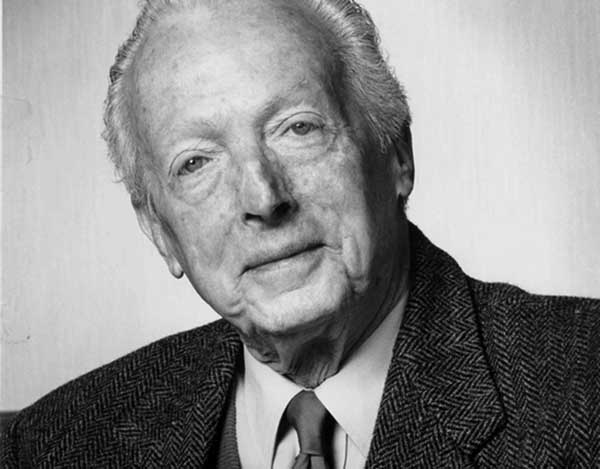

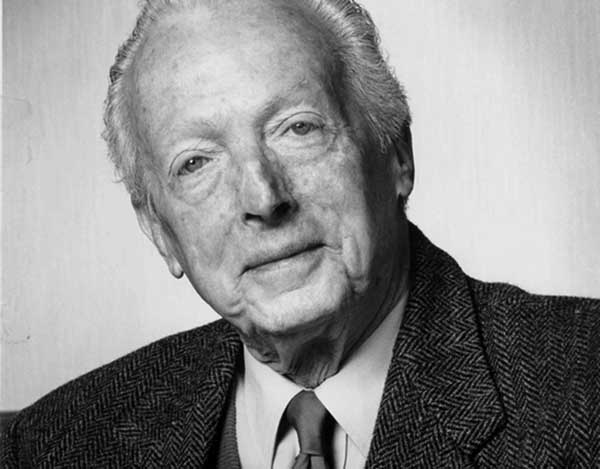

Two friends of Bill Ash, who died last month aged 96, share some memories of the Party’s first editor...

Bill Ash, 1917 – 2014

WORKERS, JUNE 2014 ISSUE Back in the mid-1960s when we first met him, Bill was talking about a failed and farcical attempt to set up a new communist party in Britain. He said that in his opinion success would only come if led by Reg Birch, toolmaker and veteran leader of the London Region of the Amalgamated Engineering Union, and he was waiting for Reg to make his move.  Bill Ash, a founder member of the CPBML and the first editor of The Worker. Bill Ash, a founder member of the CPBML and the first editor of The Worker.

Bill had grown up in Texas and found himself in the late 1930s with a university degree and a conviction that the most worthwhile thing to do in life was to fight fascism. The problem was that fascism was in Europe and he was in America.

In September 1939, reluctantly, the British Government declared war on Germany. Suddenly Bill saw a way forward. Canada, which in World War 1 had lost brownie points by not joining in until two years after the war started, this time waited only one week.

Bill made his way to Canada, signed on in the Royal Canadian Air Force, learned to fly, turned out to be very good at it, and in 1941 was sent to Britain to fly Spitfires with 411 Squadron. In 1942 he was shot down over France and spent the rest of the war either as a prisoner-of-war or an escapee from prison camps. His adventures, including twice being sentenced to death, also his postwar life in India just after its independence and then in London, were later described in his autobiography, A Red Square (London: Howard Baker, 1978).

Bill was not the typical show-off autobiographer, carefully shaping his past to fit his present aspirations; he presents himself as in many ways a clown, socially inept, just happening to find himself in extraordinary world-significant events in Europe and the Indian subcontinent, yet the observant, cultured and humorous person is always there.

Bill had learned a lot fighting fascists, neo-colonialists and racists but he had no experience of an organised working class such as the British. When he got to know Reg Birch and began finding out about the class here and its long history of struggle, he was very surprised.

He and Birch used to meet in a Camden Town wine bar, where he said he couldn’t hear half of it for the noise, and couldn’t quite understand the other half. But he knew it was important enough to be worth the struggle to understand. And he understood enough that, when challenged that the Party was too small, he used to reply, “It isn’t the Party that makes the revolution, it’s the working class.”

At Easter 1968 Bill attended the founding Congress of the CPBML, called by Birch. In January 1969 the Party launched its newspaper The Worker, with Bill as its editor until he retired in the mid-1980s. First a monthly, he moved it in the early 1970s to fortnightly and then weekly publication.

Journalist and editor

This man was an established novelist, a poet, a playwright and a moral philosopher. He wrote later: “I always intended to be a writer but I never intended to be a journalist”. But the Party needed a journalist and an editor for its newspaper, so Bill became both, overseeing the production of each issue and, in the early days, writing much of it himself – and unpaid, because no member who works for the Party gets paid.

In time, as the Party grew, the external printers tried to interfere with the content, so all production processes were taken in-house. (In 1997 the publication format changed to that of a magazine, the title to Workers and its frequency back to monthly, as it remains to this day.)

When Bill was in India he was there as the BBC representative. He worked for the Corporation for the rest of his career but, where others hope to progress upwards, his movement (the BBC being the BBC and Bill not covering his political tracks) was ever downwards. At the end he was a script reader of other people’s radio plays – a job he actually found extremely fulfilling and stimulating (but that paid very little).

Bill was always active in his trade union, the Writers’ Guild, its co-chairman twice, and in his honour the Guild is introducing what it plans to call “B ASH” awards for new writers. ■

|

|

From Booklist

From Booklist