|

|

Post by dodger on Sept 6, 2013 14:51:36 GMT

The destruction of the old Highland society took with it not only a class opposing the rise of the bourgeoisie – the feudal Scottish clan leaders – but also trampled on the rights and well-being of tenant farmers trying to eke out a living...

The Highland Clearances

WORKERS, JUNE 2011 ISSUE

The Highland Clearances offer an example of the way class contradictions are resolved by the tyranny of capitalism. The ending of the clan system helped pave the way for the rising industrial bourgeoisie to focus its attention on developing industry rather than defending its internal borders. In the process of enclosing vast tracts of land for sheep, the tenant farmers were forcibly removed and thousands transported.

A significant event in this process was the clashing of two armies, representing contrasting economic systems, at Culloden Moor in the Scottish Highlands in 1746. The Duke of Cumberland’s forces, acting for King George’s government, routed Prince Edward’s Jacobite army, last hope of the exiled Stuarts. In doing so they broke decisively the power of ancient, tribal clanship that had existed in Highland society, bringing into line the final area out of kilter with the rest of bourgeois Britain. After Culloden, the Highlands were refashioned and incorporated into a modern, capitalist environment.

The old order broken

Following Culloden, the ancient feudal rights and organisation of the clans were abolished. No exception was made: the Gordons, who had stayed loyal to King George, were treated no differently from the other clans. Even the most harmless symbols of clan loyalty were prohibited: wearing the kilt and playing the bagpipes were forbidden, a ban not lifted for 30 years. The intention that “a sheriff’s writ should run” in the Highlands as certainly as it ran everywhere else was achieved. Subsequently, all the Highlands observed the laws of the bourgeois parliament in Whitehall and lived on the same system as the whole of Britain.

Almost immediately, roads were constructed that made the demise of the highland clans complete. Between 850 to 1500 miles of roads were hastily built; in effect military, strategic roads that split the block of Highland clans into fragments. This extinction of the older society completed a process started long before, which alone made it possible for Britain in the next hundred years to become the workshop of the world. There were now no feudal lords to be conciliated or cajoled by the rising employing class.

Clearances and suppression

The Highland society, which had operated for generations, made no economic sense to modern bourgeois ways. Tenant farmers scratched a living off the rugged terrain, paying only small rents to chiefs whose wealth did not match that of their lowland contemporaries. By the end of the 18th century, the surviving chiefs and new landowners realised that serious profit could never be made that way.

In England the capitalist agrarian revolution was transforming agriculture. New farming techniques and mechanisation together with enclosure of formerly common land made farming more productive and profitable. These property upheavals had been going on in England since the 17th century in a much more gradual way. In the Highlands, however, these agrarian improvements had been delayed, partly because some landowners were too poor to put them into practice, partly due to the complex clan system that regulated and restrained Highland society.

The Battle of Culloden, painted by David Morier two years after the event.

With sudden rapidity the Highlands were driven through a series of changes that had taken hundreds of years in England. After 1746 harsh suppression and legal measures undermined and destroyed what remained of the clan system. Realising that their old ways were over, the clan chiefs transformed themselves into landlords who saw their clan retainers as an unprofitable expense. Landowners began to view their territory as a source of economic revenue instead of military men. More became absentee landlords and sought to convert their acres into cash.

The cry of “sheep devour men” was heard again. Landlords slowly disengaged themselves of all their followers who could not be used as shepherds or compelled to rent small farms. A first big clearance took place on the Drummond estates in Perthshire in 1762. In 1782 the Glengarry estates, Inverness-shire, followed suit with the rent roll rising from £700 to £5,000 in 32 years. It is estimated that as many as 200,000 people were evicted in clearances by the turn of the century. These early clearances were for sheep; later ones were for deer. Between 1811 and 1821, some 15,000 tenants were removed from the 1.5 million acres of the Countess of Sutherland’s estates. Buildings were set alight to force the tenants to leave; many were herded onto ships. Many thousands of Highlanders left their homes and were forced to make new lives on the Scottish coastal plains, in the Scottish lowlands or across the oceans. Some were drawn to the burgeoning industrial revolution: for instance, many went to work at the New Lanark Mills that opened in Lanarkshire in 1784. The clearances continued until the mid-19th century, when most farmers had been cleared.

Cheviot sheep, bred for toughness and able to thrive in difficult weather conditions, could generate large incomes, perhaps more than ten times as much as cattle on the same land. But the tenant farmers had to be removed. Many, who retained their loyalty to the chiefs, complied. Those who objected found they had limitations imposed upon them.

Landowner laws

The law strongly favoured the landowners: the farmers had no leases and were merely tenants at will who could be evicted from their homes with only minimal notice. There were incidents of resistance. In some cases brutal methods were used to evict tenants. The armed forces were called upon by landowners in times of trouble.

As it transpired, landowners needed funds to carry out the clearances and the returns from sheep farming were only temporary. Indeed, by the end of the nineteenth century that industry had collapsed and the Highlands were drastically depopulated. Its economy still does not thrive to this day. The callous land grabs in the Scottish Highlands were not accidental but flowed from capitalism’s drive to displace and uproot all pre-existing economic forms, to remake everything in its own image, and crush everything getting in the way. We can learn from this and be warned!

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Dec 11, 2013 18:11:24 GMT

Brilliant account of the Darien disaster and finance capital's responsibility, 11 Dec 2013

This Will Podmore review is from: The Price of Scotland: Darien, Union and the Wealth of Nations (Paperback)

Douglas Watt has written a splendid account of the Darien disaster and its influence. In 2008, this book won the Hume Brown Senior prize in Scottish History, Scotland's most prestigious history award. From 2003 to 2006 the author was a post-doctoral research fellow in the Scottish History department of Edinburgh University, funded by the Stewart Ivory Foundation to research the financial aspects of the history of the Company of Scotland (Darien Company).

In 1695 the Scottish Parliament passed an `Act for a Company Tradeing to Affrica and the Indies', the Company of Scotland, a joint-stock company which promised to develop colonies and boost Scotland's economy. A large number of investors - nobles, landowners, merchants, ministers of the Kirk, lawyers and institutions - invested in the Company.

With the financial revolution of the 1690s and the explosion of capital markets, the first stock market boom became a true mania: they raised £400,000, four times the Scottish government's annual revenue. Then followed the financial storm of 1696-97, and harvest failures in 1695, 1696 and 1698, causing dearth and famine. The Company ran out of money in 1701.

The Company was badly managed: "in order to persuade investors that the shares were a worthwhile investment, an expensive fleet was constructed, but in order to pay for the impressive fleet, foreign investors were required. This was a very high risk circular strategy ..." No assets were insured and the location was not surveyed.

Watt comments, "The second `management' phase was truly disastrous. ... Significant mismanagement of the cargo and provisions on the first expedition followed and the climate and location proved calamitous. ... The failure of the colony and the loss of all the capital was principally the result of decisions taken by the directors. ... The directors lost touch with reality, influenced by the manic overconfidence of the nation."

Darien was "a disease-ridden jungle with a poor harbour abandoned by the Spanish nearly two centuries before". The venture proved to be a fiasco. It cost 2,000 lives, eleven ships out of 14, and more than £150,000.

The directors, unsurprisingly, tried to blame it all on the English: "A vigorous propaganda campaign was launched by the directors to deflect blame from themselves onto the English government."

The Westminster government gave the shareholders of the Company back all that they had invested in 1696, plus 43 per cent in interest payments, by the 15th article of the Treaty of Union. "This was an extraordinarily handsome return for the shareholders - a bailout of 142 pence in the pound - and was a truly incredible result for the directors, who had squandered the capital of the Company and now, as major shareholders, were to be generously rewarded for their mismanagement." As Watt observes, "the directors who were responsible for squandering the capital received the largest payouts."

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Feb 4, 2014 6:58:32 GMT

This month we review two books, one about Scotland’s past, the other about its possible future...

How speculators ruined ScotlandWORKERS, FEB 2014 ISSUE The Price of Scotland: Darien, union and the wealth of nations, Douglas Watt, hardback, 312 pages, ISBN 978-1-9-0522263-6, Luath Press Limited, 2007, £19.

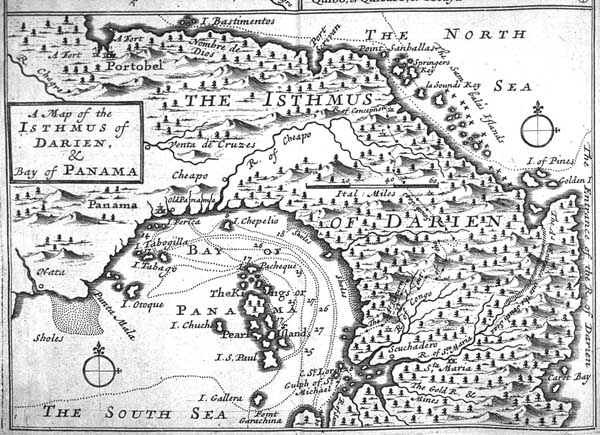

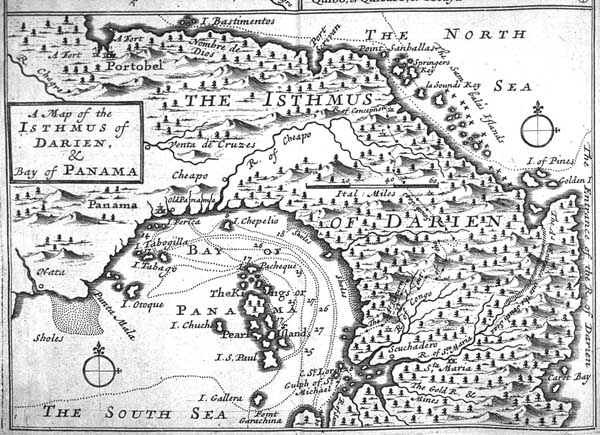

A map of Isthmus of Darien made in 1697. The disastrous colonial speculation

by Scottish investors ended with a Westminster bailout on advantageous terms.

Douglas Watt has written a splendid account of the Darien disaster and its influence. In 2008, this book won the Hume Brown Senior prize in Scottish History, Scotland’s most prestigious history award. From 2003 to 2006 the author was a post-doctoral research fellow in the Scottish History department of Edinburgh University, funded by the Stewart Ivory Foundation to research the financial aspects of the history of the Company of Scotland (Darien Company).It was at Darien in modern-day Panama that Scottish speculators – landlords and nobles for the most part – planned a colony, to be called “Caledonia”. Its rapid ruin played a large part in persuading Scotland to accept the Act of Union, and nationalist mythology still presents it as some kind of English trick.

In 1695 the Scottish Parliament passed an “Act for a Company Tradeing to Affrica and the Indies”, the Company of Scotland, a joint-stock company which promised to develop colonies and boost Scotland’s economy. A large number of investors – nobles, landowners, merchants, ministers of the Kirk, lawyers and institutions - invested in the Company.

With the financial revolution of the 1690s and the explosion of capital markets, the first stock market boom became a true mania: they raised £400,000, four times the Scottish government’s annual revenue. Then followed the financial storm of 1696-97, and harvest failures in 1695, 1696 and 1698, causing dearth and famine. The Company ran out of money in 1701.

The Company was badly managed: “in order to persuade investors that the shares were a worthwhile investment, an expensive fleet was constructed, but in order to pay for the impressive fleet, foreign investors were required. This was a very high risk circular strategy ...” No assets were insured and the location was not surveyed.

Watt comments, “The second ‘management’ phase was truly disastrous... Significant mismanagement of the cargo and provisions on the first expedition followed and the climate and location proved calamitous... The failure of the colony and the loss of all the capital was principally the result of decisions taken by the directors...The directors lost touch with reality, influenced by the manic overconfidence of the nation.”

Darien was “a disease-ridden jungle with a poor harbour abandoned by the Spanish nearly two centuries before”. The venture proved to be a fiasco. It cost 2,000 lives, eleven ships out of 14, and more than £150,000.

The directors, unsurprisingly, tried to blame it all on the English: “A vigorous propaganda campaign was launched by the directors to deflect blame from themselves onto the English government.”

The Westminster government gave the shareholders of the Company back all that they had invested in 1696, plus 43 per cent in interest payments, by the 15th article of the Treaty of Union.

“This was an extraordinarily handsome return for the shareholders – a bailout of 142 pence in the pound – and was a truly incredible result for the directors, who had squandered the capital of the Company and now, as major shareholders, were to be generously rewarded for their mismanagement.”

As Watt observes, “the directors who were responsible for squandering the capital received the largest payouts.” ■

............................................................ Scotland’s Choices: the referendum and what happens afterwards, by Iain McLean, Jim Gallagher and Guy Lodge, paperback, 223 pages, ISBN 978-0-7486-6987-5, Edinburgh University Press, 2013, £14.99.

This excellent book is a study of the implications of the referendum for Scotland’s, indeed Britain’s, future. Iain McLean is a Professor of Politics at Oxford University. Jim Gallagher and Guy Lodge are both Gwilym Gibbon Fellows at Nuffield College, Oxford.

They point out that EU treaties oblige member countries to have a central bank. The SNP says the Bank of England would be Scotland’s central bank.

The SNP says that its 3 per cent corporation tax cut would lift output by 1.4 per cent, jobs by 1.1 per cent (27,000) and investment by 1.9 per cent – by 2034! But to take advantage of lower corporation tax, all a company has to do is set up a shell company to move its taxable profit, not any jobs or actual production, to the cheaper country.

The Scottish government has made no effort to devolve labour market law. It clearly supports the present anti-trade union laws.

Scotland also has higher levels of public spending than the rest of Britain. Its domestic tax revenues per head are the same as the British average. It would rely on current oil revenues to support its public spending. As the authors conclude, “with oil revenues at their 2009-10 level, an independent Scotland would have either to raise taxes or cut services, or both.” |

|