|

|

Post by dodger on Sept 11, 2013 15:25:39 GMT

Britain was the first country to industrialise. That was before our rulers turned against manufacture...

The Industrial Revolution and the transformation of Britain

WORKERS, MAY 2012 ISSUE

Astonishing, unprecedented changes occurred in 18th and 19th century Britain, which heralded an utterly different way of life. Britain was the first country to become an industrial nation and embrace a mechanical age. Its industrial revolution broke a tradition of economic life rooted in agriculture and commerce that had existed for centuries.

Britain was the first to industrialise because a conducive mix of internal circumstances cleared away hindrances: there was a national identity, the peasantry had disappeared, tenant farmers and labourers weren’t so tied to the land, feudal regulations had gone, there was free trade across the country, a commercial revolution had taken place, the Civil War had ended royal monopolies, the aristocracy was involved in commerce and capitalist farming, our island was free of foreign armies with lots of natural resources, rivers and ports.

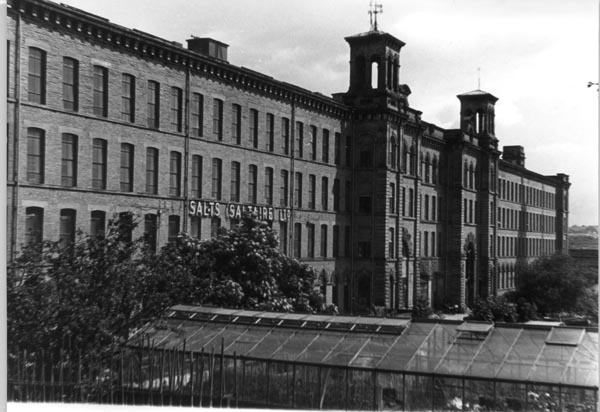

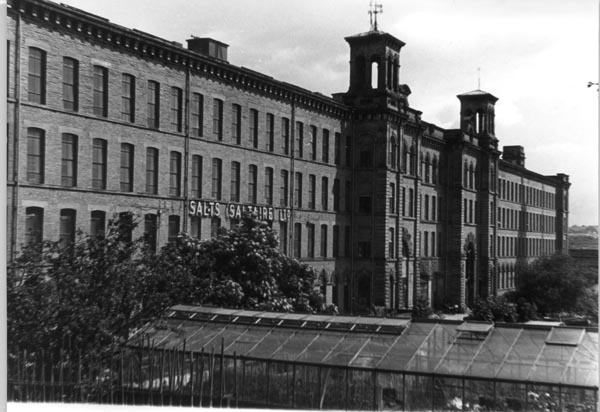

Salt’s Mill, Bradford: the textile mill was built in 1851. Now it’s a heritage centre...

Photo: Workers

There was a leap forward in society. Previously the only sources of power available had been wind and water, human and animal strength. These were gradually displaced by machines and inanimate power. Industrialisation demanded new skills, especially in the precision engineering, machine tool and metal-working trades.

New expertise was needed to build and maintain machinery, operate boilers, drive locomotives, mine coal and tend spinning-mules and power-looms. Work grew more specialised, while the new type of worker could command high wages, belong to a trade union, maintain a family and aspire to education.

There was a spectacular trans-formation of the coal, iron and textile industries with the development of steam power to drive machinery, as in the cotton industry, which had an amazing effect on the productive energies of the nation. Factories no longer had to sit by rivers, and could run 24 hours a day with shifts.

The factory system developed fast in the textile areas of Lancashire, Yorkshire, the East Midlands and in certain parts of Scotland. Fresh sources of raw material were exploited. Capital increased in volume and a banking system came into being.

Coal was the fuel of the industrial revolution. Production doubled between 1750 and 1800, then increased twenty-fold in the nineteenth century. Pig-iron production rose four times between 1740 and 1788, quadrupled again during the next twenty years and increased more than thirty fold in the nineteenth century.

The inventors of the new machines – people like James Watt, James Hargreaves, Richard Arkwright, Samuel Crompton, Edward Cartwright – were as much products as producers of the new conditions. As conditions grew ripe, the great technical inventions came. A combination of rapidly expanding markets, a supply of available wage labour and prospects of profitable production set many minds to work on the problem of increasing the output of commodities and making labour more productive.

Child labour

Child labour was widespread during industrialisation, particularly in textiles. In the early 18th century it is estimated that around 35 per cent of ten-year-old working class boys were in the labour force, rising to 55 per cent (1791 to 1820) and then almost 60 per cent (1821 to 1850). Factory owners were looking for a cheap, malleable, fast-learning labour force and found them among the children of the urban workhouses, who were only lodged and fed, not paid.

Industrialisation allowed the population to increase rapidly. In 1700 Manchester, Salford and suburbs had perhaps a population of 40,000; by 1831, it was nearly 238,000. Other great manufacturing centres underwent a similar swift expansion and often hamlets grew into populous towns. The estimated population of England and Wales in 1700 was about 5 million; in 1750, 6 million; in 1801, 9 million; in 1831, 14 million. In 1801, there were only 15 towns with a population of over 20,000 inhabitants; by 1891 there were 63.

Advances in farming such as an increase in the acreage of land under cultivation, crop rotation, machines for planting seeds, selective breeding of animals and better use of fertiliser expanded food production. Forced enclosures of land concentrated it into the hands of bigger landowners. That was blatant robbery but the process produced enough food for those flocking to growing industrial cities and meant smallholders became either hired labourers or worked in industry.

The balance of population shifted from the south and east to the north and midlands. Men and women born and bred in the countryside came to live crowded together as members of the labour force in factories. Mass production demanded popular consumption. Average incomes rose though the rich benefited more than the poor. It brought higher standards of comfort and made a wide range of consumer goods available such as matches, steel pens, envelopes, etc.

The increasing demands of industry meant that good communications were of fundamental importance in order to transport things and people. The difficulty of travel that was typical of medieval times onwards was ended. Better surfaced roads, canals, steam packets at sea and eventually railways transformed the economy and people’s lives. The village was no longer the world.

The transformation caused by the industrial revolution brought suffering as well as improvement, notably in the long working hours, overcrowded urban conditions and use of child labour. But life had been harsh in the preceding rural existence where individuals were left to fend largely for themselves. The industrial revolution concentrated attention on economic and social defects and brought collective solutions to the problems people faced whether through the formation of trade unions, a factory inspectorate or demands for health and urban planning.

Britain was for a while “the workshop of the world”. Latterly its rulers have destructively turned against manufacture. Now, wanting a future, the people and manufacturers must press for its return. ■www.workers.org.uk/features/feat_0512/industrial.html |

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Dec 5, 2013 8:35:04 GMT

Much maligned, almost a byword for backwardness, the Luddites were in fact fighting for their livelihoods and self-respect at a time when trade unions were virtually illegal…

The 1810s: The Luddites act against destitutionWORKERS, DEC 2010 ISSUE Luddite machine breaking began in 1811 in the hosiery districts of the Midlands counties. Framework-knitting traditionally had been carried out in workers’ homes, though the frames belonged to the employers. Trouble arose around the making of new, cheap “cut up” hosiery and the use of a new wide frame that reduced the numbers of workers employed and also produced shoddier goods. More and more factories began installing machinery and increasingly handloom weavers were thrown out of work.

The mill owners in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire suddenly began receiving letters threatening the destruction of their machines. These proclamations were signed in the name of Ned Ludd, or sometimes General Ludd and his Army of Redressers. Threats did not remain idle but were translated into physical action. Under cover of darkness and in a disciplined manner, bands of men attacked mills and factories with a military precision to destroy the mechanical looms (‘frames’) that were cutting their wages and putting them out of work.

A still-working spinning mule at Quarry Bank Mill, Cheshire. The introduction of power looms massively increased the supply of cotton yarn, undermining the traditional livelihoods of the handloom weavers.

In Nottingham over a three-week period in March 1811, more than two hundred stocking frames were destroyed by workers upset by wage reductions and the use of un-apprenticed workmen. Several attacks took place every night and 400 special constables were enrolled to protect the factories; even £50 rewards (a phenomenal sum for the time) were offered for information.

Action against machines quickly spread north to Lancashire and the West Riding of Yorkshire, and into Leicestershire. Contemporary accounts indicate that bands of machine-breakers were huge, numbering hundreds or sometimes thousands of people. Unlike the Midlands, the offending machines in the cotton and woollen industries of the northern counties were chiefly to be found in factories rather than workers’ houses, hence under the direct protection of employers’ hired guards, which led to more violent, often less successful acts.

In Yorkshire in the 1810s, the croppers – a highly skilled group of workers who produced the cloth’s fine finish – turned their anger on the new shearing frames.

Their most notable attack took place at Rawfolds Mill near Brighouse in April 1812. Two croppers and a local mill-owner lost their lives; three croppers were transported and fourteen were hanged. In February and March 1812, factories were attacked in Huddersfield, Halifax, Wakefield and Leeds. Throughout 1812, activity also centred on Lancashire cotton mills where local handloom weavers objected to the introduction of power looms.

Thousands of troops

In an attempt to control these widespread Luddite manoeuvres, there were in 1812 as many as twelve thousand troops deployed by the government in the four northern counties – more troops than Wellington had available in Spain that year to fight Napoleon’s armed forces! Luddites met at night on the moors surrounding the industrial towns, where they rallied, manoeuvred and drilled their forces. They enjoyed, particularly in the early years, extensive popular support in the immediate community.

Luddism was not the first example of attacks on new machinery in Britain. Sporadic machine breaking had occurred long before the Luddites, particularly within the textiles industry. Indeed, Hargreaves and Arkwright had had to move to Nottinghamshire, away from open animosity in Lancashire. But the industrial revolution by this time was adding to the misery and causing the movement. Bad housing, employment of women and children at cheap rates, insanitary and unsafe conditions in factories and mines, and the replacement of labour by machines all played their part in the distressed state of the people. The ongoing Napoleonic Wars also added to their desperate plight when Napoleon’s blockade prevented British manufacturers and traders from selling their goods, having a destructive effect on the cotton industry.

Employers cut wage bills, workers were sacked and machines were made more use of. In addition, there was a series of bad harvests (1808-12). Food prices rocketed and food riots broke out in 1812 in places like Manchester, Oldham, Ashton, Rochdale, Stockport and Macclesfield. (A load of potatoes could cost twenty weeks wages.) Great economic distress subjected workers to “the most unexampled privations”. From being among the most prosperous of workers, handloom weavers quite suddenly found themselves facing destitution.

The government introduced a series of repressive measures to deal with the Luddites. The Frame Breaking Bill (1812) made the destruction of machinery punishable by death. Trials of suspected Luddites were held before judges who could be relied upon to hand down harsh sentences. Several dozen Luddites were hanged or transported to penal servitude in Australia. The spy system was reintroduced. The Anti-Combination Act (1799), under which trade unions were forbidden, remained in force. No wonder Luddism was characterised by one historian as “collective bargaining by riot”.

Revival

Despite the repression, further sporadic incidents occurred in subsequent years. In 1816, there was a revival of machine breaking following a bad harvest and a trade downturn. 53 frames were smashed in Loughborough. But by 1818 machine breaking had petered out.

It is fashionable to stigmatise the Luddites as mindless blockers of progress. But they were motivated by an innate sense of self-preservation, rather than a fear of change. The prospect of poverty and hunger spurred them on. Their aim was to make an employer (or set of employers) come to terms in a situation where unions were illegal. They wanted to protect a centuries-old, craft-based way of life that gave them livelihood and self-respect. Frames were left untouched in premises where the owners were still obeying previous economic practice and not trying to cut prices.

At times the Luddites did improve real wages. Luddism was a deliberate tactic employed by a self-acting, self-organising working class grappling with many desperate problems during industrial capitalism’s harsh autocratic beginnings.

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Mar 9, 2014 16:18:09 GMT

www.workers.org.uk/features/feat_0314/speenham.htmlThe end of the 18th century saw a new system that encouraged employers to pay below-subsistence wages. It was called after an area in Berkshire... 1795: The road to SpeenhamlandWORKERS, MAR 2014 ISSUE In 1597 the English parliament ruled that rogues and vagabonds (note the emotive terms) should be sent back to their parishes for punishment and forced labour. The Poor Law Acts of 1598 and 1601 inaugurated a system of poor relief based on parish responsibility and parish rates which was to last until 1834.

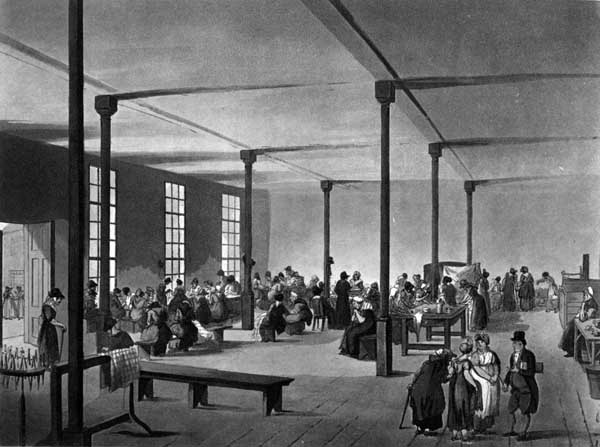

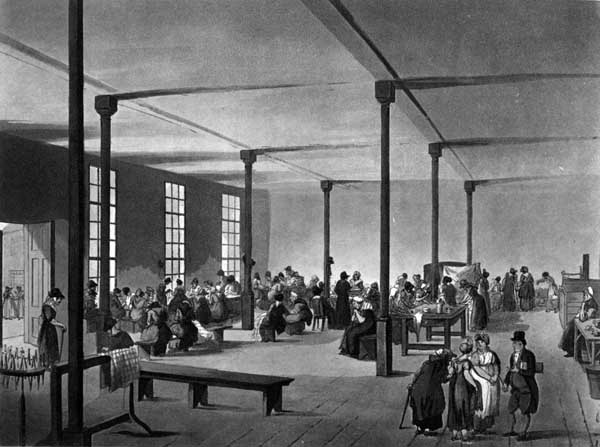

An (idealised) image of the St James’s Workhouse, London, around 1800. An (idealised) image of the St James’s Workhouse, London, around 1800.

The system encouraged Justices of the Peace (usually local employers) to fix parish wages as low as possible, as workers could be kept alive by having their wages topped up by the rates. Money for parish poor relief was raised by collecting a rate, based on the estimated value of each property, and collected by the parish constable and “overseers of the poor”.

In 1637 in John Milton’s village of Horton, a local mill-owner cost parish ratepayers £7 5s (£7.25p) a week to supplement the wages of his workers. (Little wonder that ratepayers often opposed new industries setting up in the parish.)

Later, the 1662 Settlement Laws restricted the parish obligation to look after persons who had a permanent settlement; anyone else seeking assistance had to return to the place where they were born.

In 1723 the Workhouse Test Act made the poor enter workhouses in order to obtain relief. Between 1601 and 1750 a vast, cumbersome system of poor law was created, mainly serving the interests of landowners in rural society.

The Speenhamland System

In the second half of the 18th century England’s economy and society began to be transformed. There was population growth, industrialisation requiring greater mobility of labour, and mass enclosures of land. The earlier system of poor law continued, but was amended to respond to the new conditions.

In 1782 Gilbert’s Act excluded the “able-bodied poor” from the workhouse and forced parishes to provide either work or “outdoor relief” for them. It also permitted parishes to build workhouses. “Indoor relief” (in workhouses) was confined specifically to the old, sick or dependent children.

Britain was at war with revolutionary France from 1793 until 1815. Grain imports from Europe stopped, and poor harvests in 1795-6 meant grain prices shot up. Many at the time also blamed middlemen and hoarders for the rises. Food riots marked the spring of 1795. The ruling class feared that working people might be tempted to emulate the French, and revolt. Acute social and economic distress spread throughout the rural south of England, placing strains on the poor law system.

In May 1795, magistrates in Berkshire (one of the counties most affected by enclosure) met in Speenhamland and observed, “The present state of the poor does require further assistance than has been generally given them.” Seeking to retain control over the labourers and prevent disturbances, they established a minimum level a family needed to survive and decided to use the poor rate to make up the pay of those who found themselves below the level.

Their proposed basis for “outdoor relief” was that “when the gallon loaf (8lb 11oz) shall cost one shilling, then every poor and industrious man shall have for his own support three shillings [15p] weekly either produced by his own or his family’s labour or an allowance for the poor rates and for the support of his family one shilling and sixpence”. For every penny that the loaf rose above one shilling they reckoned that a man would need three pence for himself and one penny for each member of his family. This system spread rapidly and was soon adopted or modified in many other counties experiencing social distress.

“Speenhamland” was not created to support the unemployed or eradicate poverty. It aimed to provide a (mainly rural) labour force at low direct cost to employers, using local taxation (“poor rates”) as subsidies to supplement the poverty wages of farm workers.

The system allowed employers, including farmers and the nascent industrialists of the town, to pay below subsistence wages, because the parish would make up the difference and keep their workers alive. Workers’ low incomes went unchanged. Speenhamland was a tactic to institutionalise poverty without letting it reach chronic heights or outright malnutrition.

The impact of paying the poor rate fell on the landowners of the parish concerned. It complicated the 1601 Elizabethan Poor Law because it let “working paupers” draw on the poor rates. The Berkshire magistrates had also proposed another option – that farmers and other employers should increase the wages of their employees. But that idea met with little response.

Under the Speenhamland System ratepayers often found themselves subsidising the owners of large estates who paid poor wages. It was not unknown for landowners to demolish empty houses in order to reduce the population on their lands and also to prevent the return of those who had left. At the same time, they would employ labourers from neighbouring parishes. These people could be laid off without warning but would not increase the rates in the parish where they worked.

During the 20 years after the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, attitudes to the poor began to change and the system was criticised by landed ratepayers as being expensive. Others said it impeded mobility of labour. It encouraged farmers to pay low wages and to lay off workmen in winter and re-employ them in spring and summer, as it enabled them, just, to survive.

Forced labour

A Royal Commission in 1834 called for the abolition of “outdoor” rate relief and recommended the maintenance of workhouse inmates at a level below that of the lowest paid workers – a crude piece of intimidation to everyone. The resulting 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act created a system of “indoor” relief and forced labour in a rapidly expanded system of hated workhouses. But that’s another tale.

Systems such as working tax credit and housing benefit, and the introduction of universal credits, are basically a re-enactment of the Speenhamland principle. They are another version of institutionalised poverty, a modern attempt to divert our class from trade union struggle for wages by offering paltry handouts taken from our class’s taxes (see article in May 2013 issue of Workers at http://www.workers.org.uk). ■

|

|

|

|

Post by dodger on Apr 4, 2014 5:27:12 GMT

www.workers.org.uk/features/feat_0414/workhouse.html

When landowners found that using the poor rate to supplement employers’ below-subsistence wages too expensive, they found another solution...

1834: The way to the workhouse

WORKERS, APR 2014 ISSUE

At the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 there was a massive increase in unemployment. With the introduction of the Corn Laws that set high tariffs on imported corn and led to huge price rises, the numbers claiming “outdoor poor relief” (see Workers March 2014) soared. This caused growing criticism from landed ratepayers who contributed the poor rate. So our rulers changed course.

Wanting to curtail “outdoor relief” (payments to workers outside the workhouse), the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act centred on intensifying the system of workhouses, aiming for fewer claimants. There had been workhouses before 1834 but they were not the sole method of “poor relief”. Poor Law Commissioners, who ran the new scheme, divided the country up into groups of parishes (known as poor law unions), and required them to set up workhouses providing only the most basic level of comfort. Workhouses were intended to be forbidding in order to deter both would-be inmates and outside workers. Ratepayers in each poor law union elected a Board of Guardians to manage their workhouse. Wanting to curtail “outdoor relief” (payments to workers outside the workhouse), the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act centred on intensifying the system of workhouses, aiming for fewer claimants. There had been workhouses before 1834 but they were not the sole method of “poor relief”. Poor Law Commissioners, who ran the new scheme, divided the country up into groups of parishes (known as poor law unions), and required them to set up workhouses providing only the most basic level of comfort. Workhouses were intended to be forbidding in order to deter both would-be inmates and outside workers. Ratepayers in each poor law union elected a Board of Guardians to manage their workhouse.

New workhouses were usually erected towards the edge of the union’s main town. Early union workhouses were deliberately plain as a deterrent, though as time passed more decoration appeared. They varied greatly in size, from tiny ones of 30 up to one in Liverpool that housed over 3,000.

Buildings were specifically designed to separate the different categories of inmate (known as “classes”) – male and female, infirm and able-bodied, boys and girls under 16, children under seven. Buildings, doors and staircases were arranged to prevent contact between these classes.

Apart from concessions made for some contact between mothers and children, the different categories lived in separate sections and had separate exercise yards divided by high walls. The one communal area was the dining-hall. But segregation still operated with different seating areas and sometimes there was a central screen dividing men and women.

You were not “sent” to the workhouse. Theoretically entry was voluntary – you were only impelled by the prospect of starvation, homelessness and general misery. Before the social provisions introduced much later, many elderly, chronic sick, unmarried mothers-to-be, abandoned wives or orphaned children had no other option. However, it was viewed as a last resort because of the social stigma attached and the general fear of never getting out. Particularly for the elderly, it was a place you never came out of, only concluded by burial in an unmarked pauper’s grave, often without mourners. Workhouses were not prisons; inmates could leave at any time after giving a brief period of notice. As with entry, however, families had to leave together.

Harsh

It was a harsh regime. On arrival people’s clothes were taken away and a workhouse uniform issued. Daily life was strict with early rising from 6am and early bedtimes at 8pm. Sleeping was in dormitories with beds packed together. In London’s Whitechapel workhouse in 1838, 104 girls were sleeping four or more to a bed in a room 88 feet long, 16 and a half feet wide and 7 feet high. Life was governed by rules with penalties for those who broke them.

In return for board and lodging, adult workhouse inmates were required to do unpaid work in the workhouse and its grounds six days a week. Women were employed either in workhouse domestic chores such as cleaning, preparing food, laundry work, making and maintaining uniforms, or nursing and supervising young children. Able-bodied men were employed in manual labour, often strenuous but with little practical value such as stone-breaking, corn grinding, oakum picking or bone-crushing. Rural workhouses cultivated surrounding land. For older or less physically able inmates a common task was the chopping and bundling of wood for sale. Some poor law unions sent destitute children to British colonies such as Canada or Australia. Food was very basic and intended to make life outside seem an attractive option: bread was a staple, porridge or gruel for breakfast, meals were often cheese or broth.

There was resistance to the new poor law in northern manufacturing districts of East Lancashire and West Yorkshire and parts of Wales, where workhouses were often viewed as ineffective, either standing empty in good times or overwhelmed by claimants in periods of downturn. Employers preferred to give short-term handouts (dole) allowing families to stay in their houses until conditions improved. Towns such as Bradford and Huddersfield saw opposition with attacks on poor law officials and running battles with army troops.

According to an 1861 parliamentary report, 14,000 of the total adult workhouse population of 67,800 had been there for more than five years. By 1901, 5 per cent of the nation’s over-65s were living in a workhouse. In rural areas, workhouse populations generally rose in winter and fell in the summer.

In later decades various campaigns including one by the Workhouse Visiting Society brought some improvements. Workhouse responsibilities were transferred to local councils and then abolished in 1929 and 1930. Memories of workhouse indignities were so loathed they were passed on to succeeding generations.

|

|