Post by dodger on Dec 5, 2013 8:08:06 GMT

In 1864 delegates from across Europe met to create an international workers’ movement…

1863: The First International

WORKERS, FEB 2011 ISSUE

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the International Workingmen's Association (IWA) – sometimes called The First International – united a variety of different political groups and trade union organisations to further the prospects of the working class, initially across Europe, then America. It is probably the best (or only) example of genuine international working class cooperation organised by the workers themselves and guided by a revolutionary socialist outlook that world history has yet produced, and it has relevance for us today, particularly because of the key role English trade unionists played in it.

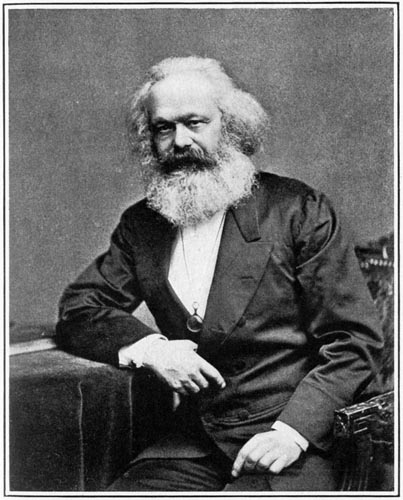

Karl Marx, one of the founders of the First International

Following the widespread Revolutions of 1848, a period of harsh reaction had set in over Europe, before the next major upswing of activity arose, presaged by the founding of the IWA in 1864. The great change came in July 1863, when at a historic meeting held in London at St. James’ Hall, French and British workers discussed developing a closer working relationship and declared the need for an international organisation. This was not only to prevent the import of foreign workers to break strikes, but also to forge continuing economic and political cooperation, invite representatives of other continental nations to join them and work to end the prevailing economic system, replacing it with some form of collective ownership.

Unanimous

In September 1864, a meeting took place in St. Martin’s Hall, with Britons, Germans, French, Poles and Italians represented in large numbers, which unanimously decided to found an international organisation of workers. Among others, George Odger (Secretary, London General Trades Council) read a speech calling for international co-operation. Karl Marx sensed the importance of this gathering and joined it, participating as a representative of German artisans residing in London. The gathering heralded a new era in the workers’ movement.

In October, a General Council – with additional coopted national repre-sentatives – was formed, meeting weekly at 18 Greek Street. Most of the British council members were trade union leaders. On the initial Council were tailors, carpenters, weavers, shoemakers, furniture makers, watchmakers, instrument makers and a hairdresser. Marx attended regularly, becoming a constant leading figure and one of the few to be regularly elected over many years, only relinquishing his position in 1872.

Difficulties arose immediately and the new organisation could easily have foundered, but Marx played a vital role in ensuring the International remained true to its founding purpose. Mazzini’s Italian delegates proposed a political programme that was against class struggle and drew up very centralised rules, fit only for a secret political society. This approach would have hamstrung the very basis of an international workers’ association, conceived not to create a movement but only to unite and weld together already existing and dispersed class movements in various countries. So instead Marx set about writing his rallying Address to the Working Classes and wrote a simplified set of rules, which were adopted.

Trade union basis

The IWA was established essentially on the basis of trade unions in a number of nations, together with a motley crew of diverse political groups with differing philosophies (including Mutualists, Blanquists, Proudhonists, English Owenites, Italian republicans, anarchists, radical democrats, and other socialists of various hues). However, over its short life, at the prompting of Marx and supported by English trade unionists, it grew into a powerful movement that coordinated support for major class actions and inspired genuine fear in the defenders of the bourgeois status quo. Many national local federations developed strong working class bases and movements. At its peak, the IWA is estimated to have had between 5 to 8 million members.

For nigh on ten years Marx provided leadership and devoted a major part of his energies to the affairs of the International, ensuring it pursued a class direction. Only the publication of Das Kapital in 1867 competed for his attention. Throughout he strove to fashion what had started as a loose alliance with divergent ideologies into a united class movement informed by revolutionary, class-based ideology. To such good effect that the “Spectre of Communism” Marx had seen haunting Europe in his and Frederick Engels’ 1848 Communist Manifesto seemed much more real to the capitalist establishment of the late 1860s than it had 20 years earlier. As political and organisational head of the International and author of the book that sought to lay bare “the economic law of motion of modern society”, Marx finally seemed close to achieving the union of socialist theory and revolutionary practice that he had always aimed for.

By the time the Geneva Congress (1866) convened, the Association could already claim credit for having successfully counteracted the intrigues of capitalists who were always ready to misuse the foreign worker as a tool against the native worker in the event of strikes. One of its great purposes was “to make the workmen of different countries not only feel but act as brethren and comrades in the army of emancipation”. This Congress’s most significant decision was the adoption of the 8-hour working day as one of the Association's fundamental demands, “a preliminary condition, without which all further attempts at improvement and emancipation are bound to founder”, which had an immediate impact in America.

Solidarity

Nowhere did the Association initiate any strikes, confining itself merely to intervening where the character of the local conflicts required supportive measures and solidarity. The International intervened significantly in several important cases.

For instance, where previously the standard threat of British/English capitalists when their workmen would not tamely submit to their arbitrary dictation had been to supplant them by an importation of foreigners, the General Council often frustrated the plans of the capitalists. When a strike or a lock-out occurred concerning any of the affiliated trades, the continental correspondents of the Association were instructed to warn the workmen in their respective localities not to enter into any engagements with the agents of the capitalists of the place where the dispute was. Consequently, the manoeuvres of the English capitalists were frustrated during the strikes and lock-outs of railway excavators, conductors and engine drivers, zinc workers, wire-workers, wood-cutters, and so on. In a few cases, such as the strike of the London basket-makers, the capitalists had secretly smuggled in labourers from Belgium and Holland. But after an appeal from the General Council, the Belgian and Dutch workers made common cause with the English workers.

French lock-out

Also in France, where trade unions had only just been legalised, the bronze-workers (a body of approximately 5,000 people) were the first to re-form a union in 1866. In February 1867, a coalition of 87 employers demanded of their workers that they resign from the union, which culminated in a lock-out of 1,500 bronze-workers.

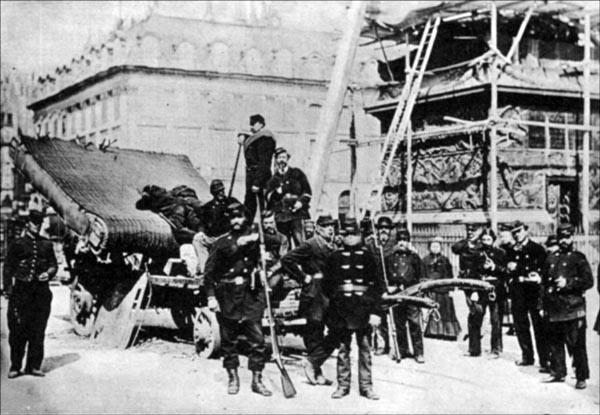

Paris, 1871: Communards about to destroy the Tour Vendôme in Paris, a symbol of imperial rule and militarism. This and other photographs were used to identify Communards who were seized and executed for their part in this act.

With their union fund being depleted, the International organised loans from the English trades unions and support from other French unions, which enabled the workers to win. Moreover, in the spring of 1868 in Geneva, building workers (whose unions were strong supporters of the International) declared a strike of block-cutters, bricklayers, plasterers and house-painters. Strikebreakers from Ticino and Piedmont were won over to the side of the workers. The masters responded by closing down the workshops in those branches of the building trade that had not yet joined in the strike and slurred the International as a foreign plot.

A number of unions, which had previously stood aloof from the International, formed sections and asked for admission. Geneva’s jewellery trade workers (goldsmiths, watchmakers, bowl-makers and engravers) then offered material aid to the building workers. The International organised support across the continent and donations flowed in.

The masters’ plan of starving out the workers failed. An agreement was reached with the masters that conceded the workers a reduction of the working time by one, and in some cases, two hours, and a wage increase of 10 per cent. The conflict resulted in a mass adherence of workmen in Switzerland to the IWA. In Belgium, the International mobilised considerable support in 1867 for the coalminers of Charleroi in Belgium who faced wage reductions and lockouts.

Paris Commune

The Paris Commune of 1871 was the first instance of the working class achieving power for itself, running Paris for over two months. Marx rose to its defence in an eloquent address published under the title, The Civil War in France. But soon after the Commune was drowned in blood, latent dissensions in the ranks of the International came to a head. The English trade unionists grew frightened, fearing association with the dramatic events in Paris; the French movement was shattered. To prevent anarchists grasping control of the IWA, the organisation was relocated to New York City in 1872, before it disbanded in 1876.

Despite the lean budgets of the General Council, all the governments of continental Europe took fright at “the powerful and formidable organisation of the International Workingmen’s Association, and the rapid development it had attained in a few years”, as the Spanish Foreign Minister of the day admitted. The IWA remains worthy of deep respect and further study. It was an authentic product of workers searching for ways to make progress; we should cherish its achievements and mimic its aim of practical cooperation.